-

On this page

Publication date: 12 October 2022

Executive summary

This report summarises the findings of the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner’s (OAIC) assessment[1] of 20 General Practice (GP) clinics (the ‘assessment GP clinics’) to identify privacy risks relevant to Rule 42[2] of the My Health Records Rule 2016 (MHR Rule) and Australian Privacy Principles (APPs) 1.2 and 11. Recommendations and suggestions were provided to each assessment GP clinic to improve their privacy posture in relation to any privacy risks identified.

Rule 42 requires healthcare provider organisations to have, communicate and enforce a written policy governing the use, security, and access of the My Health Record (MHR) system.[3] The written policy is referred to as a ‘Security and Access policy’ in this report.[4]

The OAIC considers that having a Security and Access policy is a reasonable step for healthcare provider organisations to take under APPs 1.2 and 11. Security and Access policies are critical in supporting healthcare provider organisations to protect the sensitive information of their patients. They also build staff awareness of obligations under My Health Record legislation.

The OAIC has issued guidance to assist healthcare provider organisations to comply with Rule 42 of the My Health Records Rule 2016. After fieldwork for this assessment was completed, the OAIC also published a Security and Access policy template. These, and other resources that are currently available on the OAIC and Australian Digital Health Agency (ADHA) websites, are listed in Part 3 of this report.

Although most assessment GP clinics were apparently aware of the requirement to have a Security and Access policy, it was unclear how well they understood the substantive requirements and purpose of Rule 42. Most assessment GP clinics appeared to rely on templates to prepare their Security and Access policy. While the use of templates can assist entities, they do not guarantee compliance with Rule 42. Some of the policies based on templates addressed most of the requirements of Rule 42 but were not tailored to reflect the individual practices and circumstances of the relevant GP clinic. In other cases, templates were not completed with sufficient detail to address all the requirements under Rule 42. Despite having a Security and Access policy, some assessment GP clinics also did not appear to be familiar with the content of their Security and Access policy or how to enforce it in practice.

Areas of good privacy practice that were identified for the assessment GP clinics include the following:

- Security and Access policy– 17 of the 20 assessment GP clinics had a Security and Access policy at the time of the assessment. The remaining assessment GP clinics had other policies and procedures addressing some of the substantive requirements of Rule 42.

- Managing access to the MHR system – Almost all of the policies only authorised staff to access the MHR system if they required that access to perform their duties.[5]

- Identifying a person who accesses a patient’s MHR – Most assessment GP clinics indicated that staff authorised to access the MHR system are recorded in a register and are assigned a unique identifier which is recorded each time they access the MHR system.[6]

Areas for improvement that were identified for the assessment GP clinics include the following:

- Strategies to address privacy and security risks – 14 of the 20 policies did not address mitigation strategies for identifying, acting upon and reporting MHR system-related security risks as required under Rule 42(4)(e) of the MHR Rule.

- Physical and information security measures – Nearly half of the assessment GP clinics did not follow best practice password procedures such as requiring passwords and passphrases to contain 14 or more characters.[7]

- Managing risks when supplying services to other healthcare providers – Only some of the assessment GP clinics that indicated that they supply services to other healthcare providers under contract had formal risk management procedures in relation to those other healthcare providers’ use of the MHR system, such as ensuring that they knew when and how to report MHR system-related breaches.[8]

- Potential misuse and notifications – Some assessment GP clinics disclosed potential breaches of the My Health Records Act 2012 (Cth) (MHR Act) which have not previously been notified to the OAIC. Potential unauthorised collection, use and disclosure of MHR system health information, and events or circumstances that may compromise the security or integrity of the MHR system, must be reported to the OAIC and the Australian Digital Health Agency (ADHA) as System Operator as soon as practicable.[9] The OAIC made recommendations to the relevant assessment GP clinics to remedy this as appropriate and the OAIC is considering further regulatory action to ensure any privacy risks are appropriately addressed.

Part 1: Background

The MHR system is the Australian Government's digital health record system. A MHR is an online summary of a patient's key health information including details of their medical conditions, medicines, and allergies. Healthcare provider organisations, including GP clinics, that are registered in the MHR system can view and add information to a patient’s MHR, subject to access controls set by the patient.

Rule 42 requires healthcare provider organisations such as GP clinics to have, communicate, and enforce a written policy to be eligible to use the MHR system.[10] This has been referred to as a ‘Security and Access policy’ in this report.

Security and Access policies must address several requirements including:

- the manner of authorising staff to access the MHR system

- training staff to use the MHR system accurately and responsibly, the legal obligations involved, and the consequences of breaching those legal obligations

- a process for identifying a person who requests access to a patient's MHR and communicating that person’s identity to the System Operator

- physical and information security measures, including user account management under Rule 44 of the MHR Rule[11]

- strategies to identify, mitigate and report MHR system risks

- the Security and Access policy’s version number and effective date.

Healthcare provider organisations also have obligations under the Privacy Act, including:

- APP 1.2, which requires an entity to take reasonable steps to implement practices, procedures and systems to ensure that it complies with the APPs

- APP 11, which requires an entity to take reasonable steps to protect personal information it holds from misuse, interference and loss, as well unauthorised access, modification or disclosure.

Having and enforcing a Security and Access policy in accordance with Rule 42 is a reasonable step for healthcare provider organisations to take in complying with the above APPs. The Australian Privacy Principles guidelines provides further information about the APPs.

The OAIC has published guidance on the obligations of healthcare provider organisations under Rule 42. Links to additional resources, including the Rule 42 guidance, have been provided at the end of this report.

Objective and scope of the assessment

The objective of this assessment was to examine the assessment GP clinics’ governance arrangements, in particular their Security and Access policy, and identify any privacy risks relating to Rule 42 of the MHR Rule, and APPs 1.2 and 11.

This assessment was the second of 2 assessments conducted in the MHR access security policy assessment program. The first assessment (Assessment 1) was a survey of 300 GP clinics to assess compliance with the requirement to have a written Security and Access policy under Rule 42 of the MHR Rule.[12]

Methodology

Participants in the assessment

Twenty assessment GP clinics were selected by the OAIC to participate in this assessment. They were selected from the 300 GP clinics that participated in Assessment 1.[13]

When selecting the 20 assessment GP clinics for this assessment, the OAIC ensured that:

- the sample proportionally represented all Australian jurisdictions, including metropolitan and regional areas

- GP clinics with higher volumes of uploads in the MHR System were prioritised for selection

- a variety of Security and Access policies were assessed.[14]

Conduct of the assessment

The OAIC engaged Information Integrity Solutions Pty Ltd (IIS Partners) under section 24 of the Australian Information Commissioner Act 2010 (Cth) to assist the OAIC to conduct this assessment.

The assessment involved:

- a qualitative review of each policy provided by the assessment GP clinics

- a review of the results of the survey completed by the assessment GP clinics in Assessment 1

- interviews with representatives of the assessment GP clinics

- analysis of the information provided against the requirements of Rule 42, and APPs 1.2 and 11.

The OAIC did not undertake on-site inspections and relied on the information provided by the assessment GP clinics in making any findings.

In addition to this summary report, the OAIC provided individual assessment reports to the assessment GP clinics. These assessment reports included recommendations and suggestions to address any identified privacy risks.

Part 2: Findings

General observations

Templates

Seventeen of the 20 assessment GP clinics appeared to have used a template to prepare their Security and Access policies.

However, some assessment GP clinics removed content required under Rule 42 or did not sufficiently tailor their template to the individual practices or circumstances of the assessment GP clinic or the requirements of Rule 42.

Templates can be a useful tool in developing Security and Access policies. However, using a template does not guarantee compliance under Rule 42. When using a template to prepare a Security and Access policy, healthcare provider organisations should:

- ensure that the template addresses all the requirements of Rule 42

- tailor their Security and Access policy to reflect individual practices or circumstances of the healthcare provider organisation so that it can be effectively enforced.[15]

Potential misuse of the My Health Record system

The OAIC identified the following potentially notifiable incidents from interviews held with assessment GP clinics:

- Two assessment GP clinics disclosed potential unauthorised use of health information due to misuse of the emergency access function at their clinics.

- One assessment GP clinic indicated they may have made an unauthorised disclosure of health information when uploading patient information in the MHR system.

- One assessment GP clinic also disclosed that it had experienced a ransomware attack. Such an event may compromise the security or integrity of the MHR system.

Unauthorised collection, use and disclosure of MHR system health information is a contravention of section 59 of the MHR Act.[16]

Potential breaches of section 59 of the MHR Act, and events or circumstances that may compromise the security of the MHR system, must be reported to the OAIC and the ADHA (as System Operator) under section 75 of the MHR Act.[17] Healthcare provider organisations can notify the OAIC of actual or potential breaches of the MHR system by using our Data Breach Notification form.

It does not appear that the incidents identified in this assessment were notified to the OAIC. The OAIC made recommendations to the relevant assessment GP clinics to remedy this as appropriate and the OAIC is considering further regulatory action to ensure any privacy risks are appropriately addressed.

More information is available in our guide to mandatory data breach notification in the My Health Record system.

My Health Record Security and Access policy

Areas of good privacy practice

The OAIC found that 17 of the 20 assessment GP clinics had implemented a Security and Access policy at the time of the assessment.

Figure 1 Assessment GP clinics with a Security and Access policy.

The OAIC observed that those assessment GP clinics that did not have a Security and Access policy had other procedures in place to address some of the practical requirements of Rule 42. However, these procedures varied in relation to how comprehensive they were and how they were documented.

Fifteen of the 20 assessment GP clinics communicated their policy to all relevant staff, and all the assessment GP clinics ensured their policy was readily accessible to their staff as required under Rule 42(2). Policies were generally communicated in inductions, training, and meetings, and staff could access policies through shared computer network drives, a staff intranet, and/or providing hard copies at the clinic.

Areas for improvement

Rules 41 and 42(1) of the MHR Rule require healthcare provider organisations to have a written policy to be eligible to be registered, or remain registered, under the MHR system. This policy underpins the security governance for end-users of the MHR system and ensures the protection of sensitive information.

Three assessment GP clinics did not have a Security and Access policy. In lieu of a Security and Access policy, these assessment GP clinics provided other documents (such as an APP 1 privacy policy) which did not satisfy the legislative requirements of Rule 42. Other assessment GP clinics indicated in interviews that the assessment program prompted them to implement a Security and Access policy for the first time. This is consistent with findings made in Assessment 1[18] and suggests that more could be done to increase awareness of obligations under the MHR Rule.

Access to the My Health Record system

Areas of good privacy practice

Fourteen of the 20 policies addressed a process for authorising staff to access the MHR system. Seventeen out of 20 assessment GP clinics limited access to staff who require access as part of their duties.

The majority of assessment GP clinics indicated that they would immediately suspend or deactivate user accounts if they were aware that the user account has been compromised and 13 assessment GP clinics stated this in their Security and Access policies. This reduces the risk of unauthorised access to the MHR system and is required under Rule 44(e).

Areas for improvement

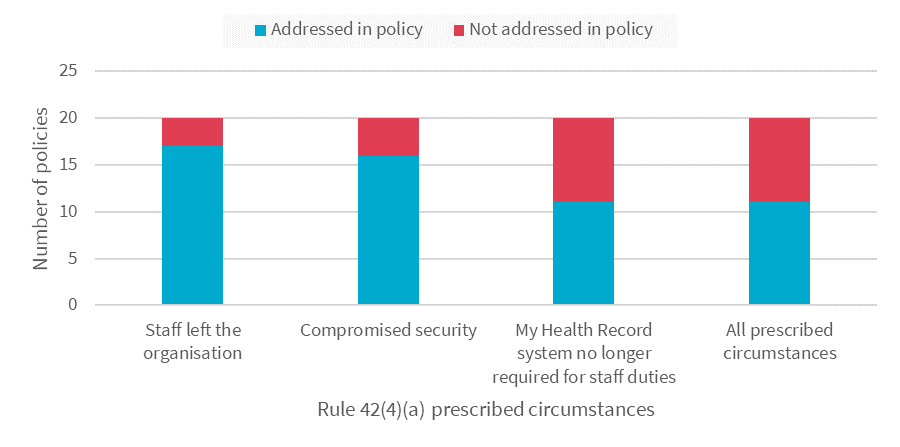

Rule 42(4)(a) requires Security and Access policies to address the manner of suspending or deactivating the user accounts of staff:

- who leave the organisation

- whose security has been compromised

- whose duties no longer require them to access the MHR system.

Overall, 9 of the 20 assessment GP clinics failed to address all the prescribed circumstances for suspending or deactivating user accounts under Rule 42 in their policies.

Sixteen of the Security and Access policies addressed processes for suspending or deactivating the accounts of users who leave the organisation or whose security is compromised as prescribed. However, only 11 of the Security and Access policies addressed suspending or deactivating the user account of a person whose duties no longer require them to access the MHR system.

Figure 2 Policies that addressed prescribed circumstances to suspend or deactivate user accounts.

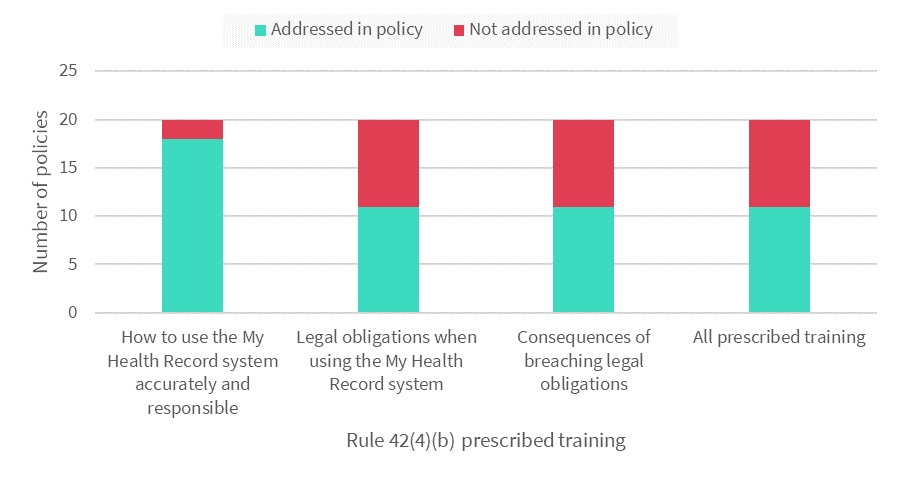

Training

Rule 42(4)(b) of the MHR Rule requires healthcare provider organisations to outline the training that they will provide to staff before they are authorised to access the MHR system. This includes training about how to use the MHR system accurately and responsibly, the legal obligations of users of the MHR system, and the consequences of breaching those obligations.

Figure 3 Policies that addressed prescribed training.

Areas of good privacy practice

Most assessment GP clinics (18 out of 20) addressed training in their policies. As required under Rule 42(4)(b), 16 of the 20 policies addressed training staff how to use the MHR system accurately and responsibly. For the majority of assessment GP clinics, this training included:

- the importance of not accessing a patient’s MHR unnecessarily (15 assessment GP clinics)

- what constitutes misuse or disclosure of patient information (13 assessment GP clinics)

- how to respond to and report suspected security or privacy issues (13 assessment GP clinics)

- accessing the MHR system in an authorised manner, including using strong passwords (12 assessment GP clinics).

Areas for improvement

In relation to training at the assessment GP clinics, the OAIC found that:

- Half of the policies did not address training about the legal obligations of users of the MHR system, and the consequences of breaching those legal obligations as prescribed under Rule 42.

- Two assessment GP clinics reported that they did not undertake any formal training.

Privacy tip

Healthcare provider organisations should provide refresher training to staff annually, in addition to ad hoc training when there are changes to legislation or MHR system functionalities. Training should be conducted regardless of the size of the organisation or how often they use the MHR system.

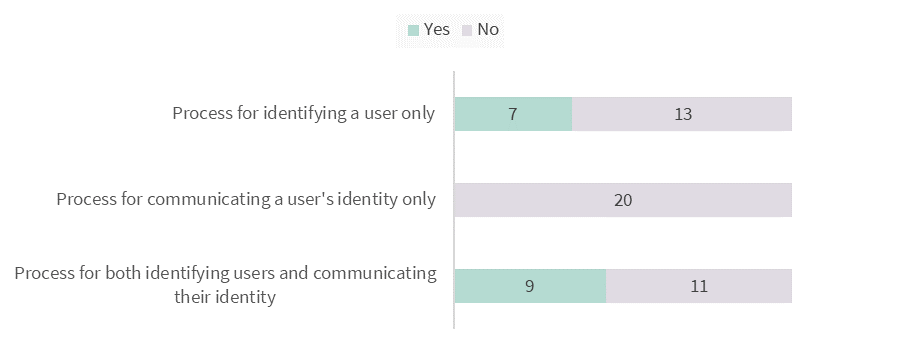

Identifying persons who request access to patient My Health Records

Rule 42(4)(c) requires Security and Access policies to address a process for identifying a person who requests access to a patient’s MHR and communicating that person’s identity to the System Operator. This ensures that the healthcare provider organisations can meet their obligations to provide certain information to the System Operator under section 74 of the MHR Act.

Areas of good practice

Almost every assessment GP clinic indicated that their staff are assigned unique internal identification codes which are captured by the organisation’s clinical software when they access the MHR system. Most of the assessment GP clinics also stated that they maintain a register of authorised users containing information such as a user’s name, internal identification code and Healthcare Provider Identifier—Individual (HPI-I).

These systems enable these assessment GP clinics to identify staff who access a MHR. However, only 14 assessment GP clinics addressed this process in their policies as required under Rule 42(4)(c).

Areas for improvement

Even where the policy outlined a process for identifying staff who access a MHR, it did not always address all relevant aspects of the procedure. For example, despite apparently doing so, 17 of the 20 policies did not state that the users’ HPI-Is are captured each time they access a MHR.

More than half of the policies did not address a process for communicating a user’s identity to the System Operator as required by Rule 42(4)(c). This indicates that more could be done by healthcare provider organisations to ensure compliance with this obligation under the MHR Act and MHR Rule.

Figure 4: Policies which addressed a process for identifying and/or communicating a user’s identity to the System Operator.

Physical and information security measures

Rule 42(4)(d) requires Security and Access policies to address physical and information security measures taken by healthcare provider organisations. This includes user account measures that must be implemented under Rule 44 of the MHR Rule, such as:

- uniquely identifying users of the organisation’s information technology systems

- having sufficiently secure and robust passwords and/or other access mechanisms.

Areas of good practice

Although they were often not addressed in their policies, most assessment GP clinics reported having some physical and information security measures, including:

- maintaining an up-to-date register of staff who are authorised to access the MHR system

- requiring a unique username and password, or a similar mechanism, to access devices and the MHR system

- automatically locking devices after a specified period of inactivity

- locking systems or user accounts after a specified number of failed logins.

Areas for improvement

Several areas of improvement were identified regarding the assessment GP clinics physical and information security measures:

- Just over half of the assessment GP clinics outlined at least one physical or information security measure in their policies. However, the policies were not comprehensive in this regard.

- While 7 assessment GP clinics confirmed in interviews that they access the MHR system remotely, none of the policies addressed accessing the MHR system remotely or any related access controls.

Privacy tip

Healthcare provider organisations should review their system functionality to determine whether it can be accessed remotely and ensure that appropriate information security measures have been implemented, even if remote access is not actively used. Measures taken should also be addressed in their Security and Access policies.

In relation to passwords or passphrases, the OAIC identified that:

- Almost half of the assessment GP clinics had passwords with less than 10 characters.

- Three assessment GP clinics did not require passwords to contain a combination of letters, numbers, and symbols.

Privacy tip

Passwords and passphrases should be changed regularly and contain 14 or more characters. This may include a combination of upper and lower-case letters, numbers, and special characters.[19]

Where possible, healthcare provider organisations should use a passphrase instead of a password. A passphrase is a string of unrelated words such as ‘crystal onion clay pretzel’. Passphrases are easy to remember, but harder to guess than traditional passwords.

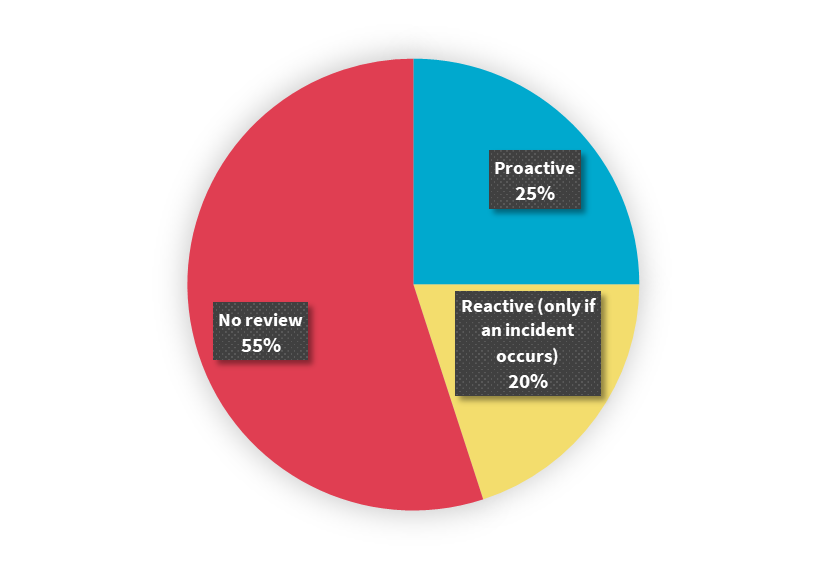

Risk management and mitigation

Rule 42(4)(e) requires Security and Access policies to address mitigation strategies to ensure MHR system-related security risks can be promptly identified, acted upon, and reported to management. Rule 42 does not prescribe specific mitigation strategies that must be addressed and enforced by healthcare provider organisations.

All the assessment GP clinics had areas of improvement in relation to risk management and mitigation.

Mitigation strategies

The OAIC found that 14 of the 20 policies did not identify any mitigation strategies as required by Rule 42.

Audit logs were used at many of the assessment GP clinics. However, to form part of an effective mitigation strategy, audit logs should be proactively and systematically reviewed.

- All but one assessment GP clinic indicated that their clinical software had audit log functionality, but few proactively used it, and none addressed reviewing audit logs as a mitigation strategy in their Security and Access policy.

- Some assessment GP clinics indicated that they were unsure of how to use this functionality.

- Eleven of the 20 assessment GP clinics reported that they did not review their audit logs, and another 4 noted that they only reviewed audit logs once they were aware of an issue such as a breach.

Privacy tip

The OAIC considers reviewing audit logs to be a good practice mitigation strategy to monitor access to the MHR system. Proactively reviewing audit logs can allow healthcare provider organisations to detect unauthorised access to the MHR system.

Audit logs are chronological records of user activity in the MHR system. They record a users’ identity, date and time of access, the patient whose MHR was accessed and the type of information that was accessed.

Figure 5: Reviewing audit logs at the assessment GP clinics.

Risk management

Having a process for responding to any suspected or actual security or privacy issues, or breaches of the MHR system, is a reasonable step in enforcing effective mitigation strategies under Rule 42(4)(e), and to protect personal information under APP 11.

It is positive that most assessment GP clinics (18 out of 20) indicated having a procedure for identifying and responding to security or privacy issues, or breaches of the MHR system. However, these processes did not always address key steps in responding to data breaches. For example, 5 of the 20 policies did not refer to a process for containing a breach, and only 2 of the policies explicitly required breaches to be assessed.

Part 3 of the OAIC’s Data breach preparation and response guidance outlines 4 key steps when responding to data breaches: contain, assess, notify and review.[20]

Complaints management

Having an effective process to manage complaints about alleged mishandling of MHR information is a reasonable step under APPs 1.2 and 11. It is also essential to identify, action and report MHR system-related security risks under Rule 42(4)(e).

Most of the 20 assessment GP clinics referred to a complaints management process in their policy. However, many of these processes did not address complaints of unauthorised access, and instead focused on scenarios where a change to a MHR was disputed by the patient.

Privacy tip

Healthcare provider organisations should ensure that their complaints management processes address complaints of unauthorised access to a MHR.

Supplying services to other healthcare providers

Although a small proportion of the assessment GP clinics supplied services to other healthcare providers, the OAIC found that this was an area for improvement in the assessment program.

Rule 42 requires Security and Access policies to be communicated, readily accessible to, and enforced against healthcare providers to whom a healthcare provider organisation supplies services to under contract. For example, if a GP clinic rents out rooms to independent doctors or other healthcare providers and provides IT facilities to access the My Health Record system, the GP clinic must enforce its Security and Access policy with these independent parties.

Four assessment GP clinics indicated that they supply services to other healthcare providers under contract. They also indicated that their Security and Access policy is communicated to those other healthcare providers. However, only one assessment GP clinic stated this in their Security and Access policy and only 2 assessment GP clinic made these policies readily accessible on a shared network drive or intranet.

Privacy tip

Healthcare provider organisations could state in their Security and Access policies whether they supply services to other healthcare provider organisations under contract. This ensures that persons who review the policy (internally and externally) can understand what risks and mitigation strategies might be relevant in relation the MHR system and how it is used in the organisation.

Security and Access policies could also state what measures the healthcare provider organisation takes when supplying services to other healthcare providers under contract. For example, healthcare provider organisations may include provisions in such contracts:

- requiring the healthcare provider receiving services to:

- comply with the organisation’s Security and Access policy

- implement physical and information security measures to mitigate the risk of unauthorised access to the MHR system

- implement mitigation strategies or processes for ensuring that security and privacy risks related to the MHR system can be identified and acted upon

- report suspected or actual breaches to the healthcare provider organisation

- allowing the healthcare provider organisation supplying services to monitor the other healthcare provider’s compliance with the above.

Review and documentation

The ongoing review and documentation of Security and Access policies was also identified as an area for improvement.

Under Rule 42(6) of the MHR Rule Security and Access policies must be reviewed at least annually and when any new or changed risks are identified. However, only 11 of the 20 assessment GP clinics had reviewed their policy within 12 months of the date of the assessment.

The quality of the reviews conducted was also found to be of concern:

- One Security and Access policy misidentified the GP clinic to which it applied.

- Four of the 20 policies did not refer to the MHR system, but instead referred to its predecessor, Personally Controlled Electronic Health Records (PCEHRs).[21]

Regularly reviewing Security and Access policies allows healthcare provider organisations to ensure that their policies are up-to-date, comply with legislative and privacy obligations, and meet community expectations.

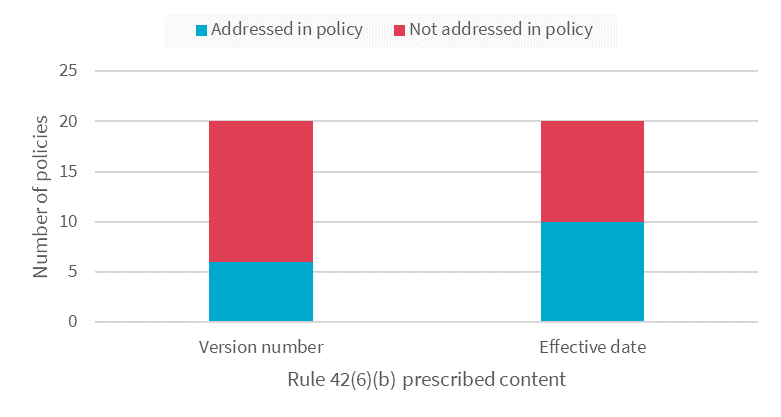

Rule 42(6)(b) also requires Security and Access policies to contain a unique version number and the effective date of that version. However, less than half of the policies reviewed complied with this requirement.

Privacy tip

In addition to the circumstances prescribed in Rule 42(6), healthcare provider organisations should review their Security and Access policies when there are changes in their organisation’s structure as a reasonable step under APPs 1.2 and 11.

Figure 6: Version numbers and effective dates in the policies.

Part 3: Additional resources

To assist healthcare provider organisation to comply with Rule 42, the OAIC has developed a Security and Access policy template that is available on our website. The ADHA, in consultation with the OAIC, has also developed an online learning module Developing a My Health Record Security and Access Policy for your Organisation. These resources were developed after the conclusion of fieldwork for this assessment.

Healthcare provider organisations should refer to Rule 42 of the MHR Rule when developing and reviewing a Security and Access policy. The OAIC and ADHA have also published useful resources on their websites. These include:

- The OAIC Security and Access Policy Guidance and Template

- The ADHA eLearning Module: Developing a My Health Record Security and Access Policy for your Organisation

- The ADHA Guidance: Implementing My Health Record in your healthcare organisation

- The ADHA Guidance: My Health Record system participation obligations, including establishing a My Health Record security and access policy

The OAIC website contains other resources to help health service providers understand and comply with their privacy and information handling obligations. These can be found on the page Privacy for health service providers which includes:

Footnotes

[1] Section 33C(1)(a) of the Privacy Act provides that the OAIC may assess whether personal information held by an APP entity is being maintained and handled in accordance with the APPs.

[2] During this assessment, the OAIC also considered Rule 41 and Rule 44 of the My Health Record (MHR) Rule 2016 to the extent that they relate to Rule 42. Rule 41 sets out the security requirements for registration, and Rule 44 concerns user account management within healthcare provider organisations.

[3] This policy may be a dedicated document, or part of a broader policy document.

[4] At the time of the assessment, these were referred to as ‘access security policies’.

[5] This is a requirement under Rules 42(4)(d) and 44(a) of the MHR Rule.

[6] These systems effectively facilitate processes for identifying persons who access a patient’s MHR and communicating that person’s identity to the System Operator as required under Rules 42 and 44(b) of the MHR Rule.

[7] For more information, the Australian Digital Health Agency’s (ADHA) fact sheet ‘Supporting a positive security culture: Passwords’ can be found at https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-11/Passwords-Supporting_a_positive_security_culture.pdf.

[8] Rule 42 places certain obligations on healthcare provider organisations that supply services to other healthcare providers under contract. An example of this is where a healthcare provider organisation supplies information technology services to individual GPs who use those services to access the My Health Record system.

[9] My Health Records Act 2012 (Cth) s 75(2).

[10] My Health Records Rule 2016 (Cth) r 41

[11] Rule 44 states that healthcare provider organisations must ensure that their information technology systems, which are used by people to access the MHR system via or on behalf of the healthcare provider organisation, employ reasonable user account management practices.

[12] The Assessment 1 privacy assessment report is available at https://www.oaic.gov.au/privacy/privacy-assessments/my-health-records-security-and-access-policy-assessment-1-general-practice-clinic-survey.

[13] More information about this sample of 300 GP clinics is available in the Assessment 1 privacy assessment report at https://www.oaic.gov.au/privacy/privacy-assessments/my-health-records-security-and-access-policy-assessment-1-general-practice-clinic-survey.

[14] In this assessment program, many of the Security and Access policies provided were similar as they were based on the same templates. Balanced against the other selection criteria, the OAIC included a range of template-based and non-template-based policies in the assessment sample.

[15] Guidance is available in Rule 42 of the My Health Records Rule 2016, the Australian Digital Health Agency’s (ADHA) Security and Access policy checklist, the ADHA’s Guide to Preparing a My Health Record system security and access policy, the ADHA’s Guide to My Health Record system participation obligations, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner’s (OAIC) Rule 42 guidance.

[16] For more information, see the OAIC’s guidance on the My Health Record Emergency access function.

[17] This obligation exists in addition to those under the Notifiable Data Breaches scheme.

[18] The Assessment 1 privacy assessment report is available at https://www.oaic.gov.au/privacy/privacy-assessments/my-health-records-security-and-access-policy-assessment-1-general-practice-clinic-survey.

[19] For more information, the ADHA’s fact sheet ‘Supporting a positive security culture: Passwords’ can be found at https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-11/Passwords-Supporting_a_positive_security_culture.pdf.

[20] More information about data breach preparation and response is available on the OAIC website at https://www.oaic.gov.au/privacy/guidance-and-advice/data-breach-preparation-and-response.

[21] The PCEHR system was replaced by the MHR system in 2015.