-

On this page

Download the report

Updated: 19 March 2025Report summary

This report by the Australian Information Commissioner examines the prevalence and use of messaging apps by Australian Government agencies. It describes a review of the policies and practices of 22 Australian Government agencies. The Commissioner has made recommendations to help agencies better meet their recordkeeping, freedom of information (FOI) and privacy obligations when using messaging apps, and support the fundamental human rights of information access and privacy oversighted and promoted by the Australian Information Commissioner.

22

agencies’ policies and

practices were reviewed

Messaging apps – such as Signal, WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger and Telegram – are an established feature of personal and professional communication. A common function of these messaging apps is the ability to send messages that disappear after a specified period.

Key findings

Agency use of messaging apps

Messaging apps are an established feature of digital communications in the Australian Public Service.

16

(73%)

of the 22 agencies permitted messaging apps for work purposes.

3

(14%)of the 22 agencies did not have a position.

3

(14%)of the 22 agencies prohibited their use.

Agency policies and practices around messaging apps

Despite being an established feature of government agency communication, the use of messaging apps is not well supported with policies and procedures that reflect statutory obligations in the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (FOI Act), Privacy Act 1988 and Archives Act 1983.

8(50%)

of the 16 of agencies that permitted the use of messaging apps had policies/procedures to support their use

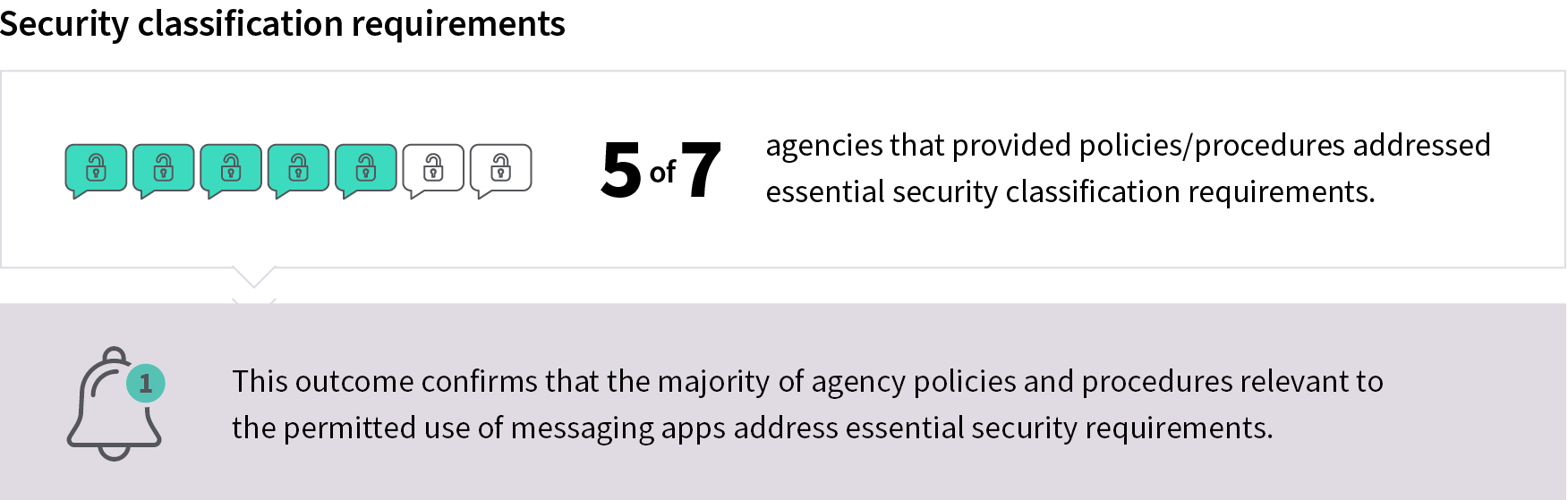

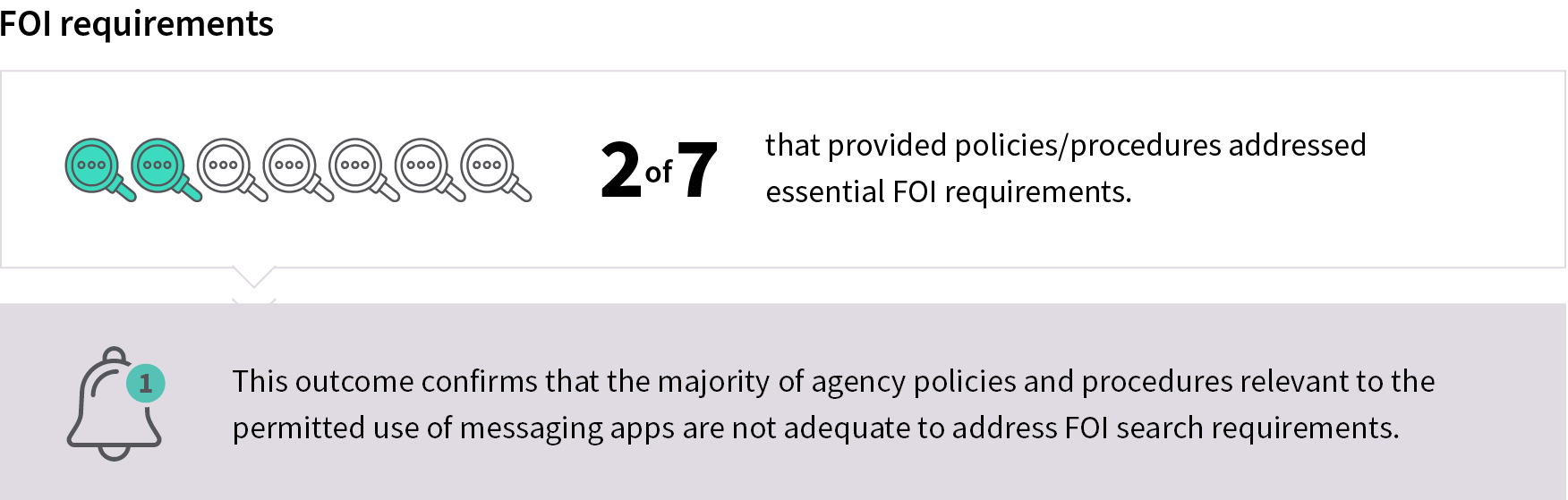

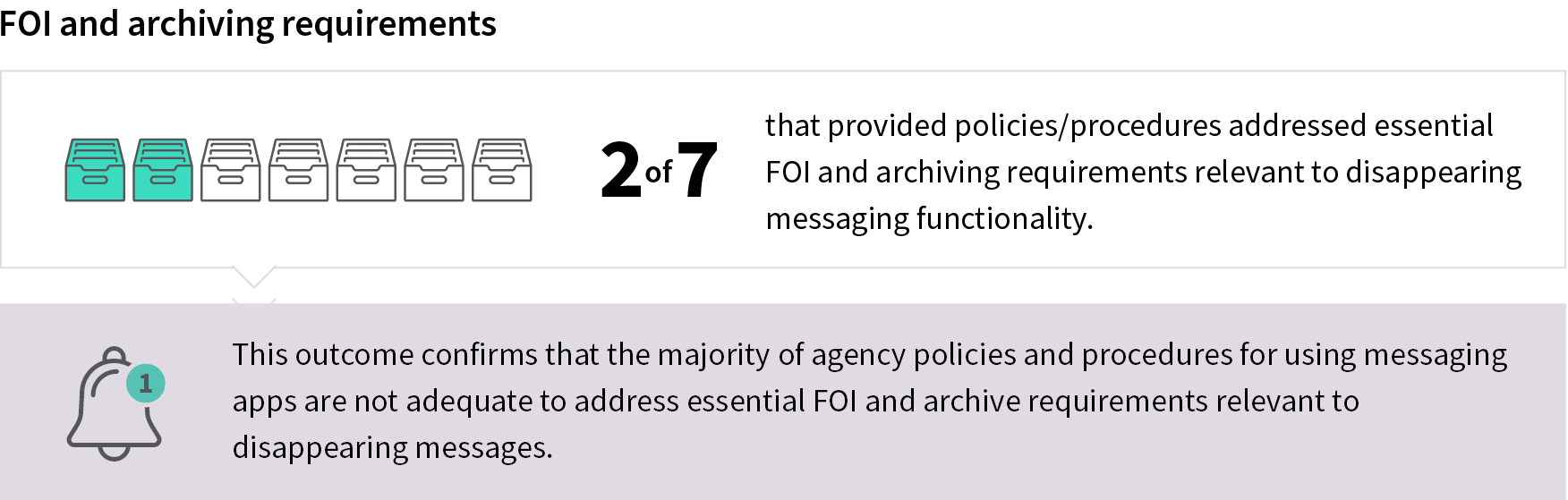

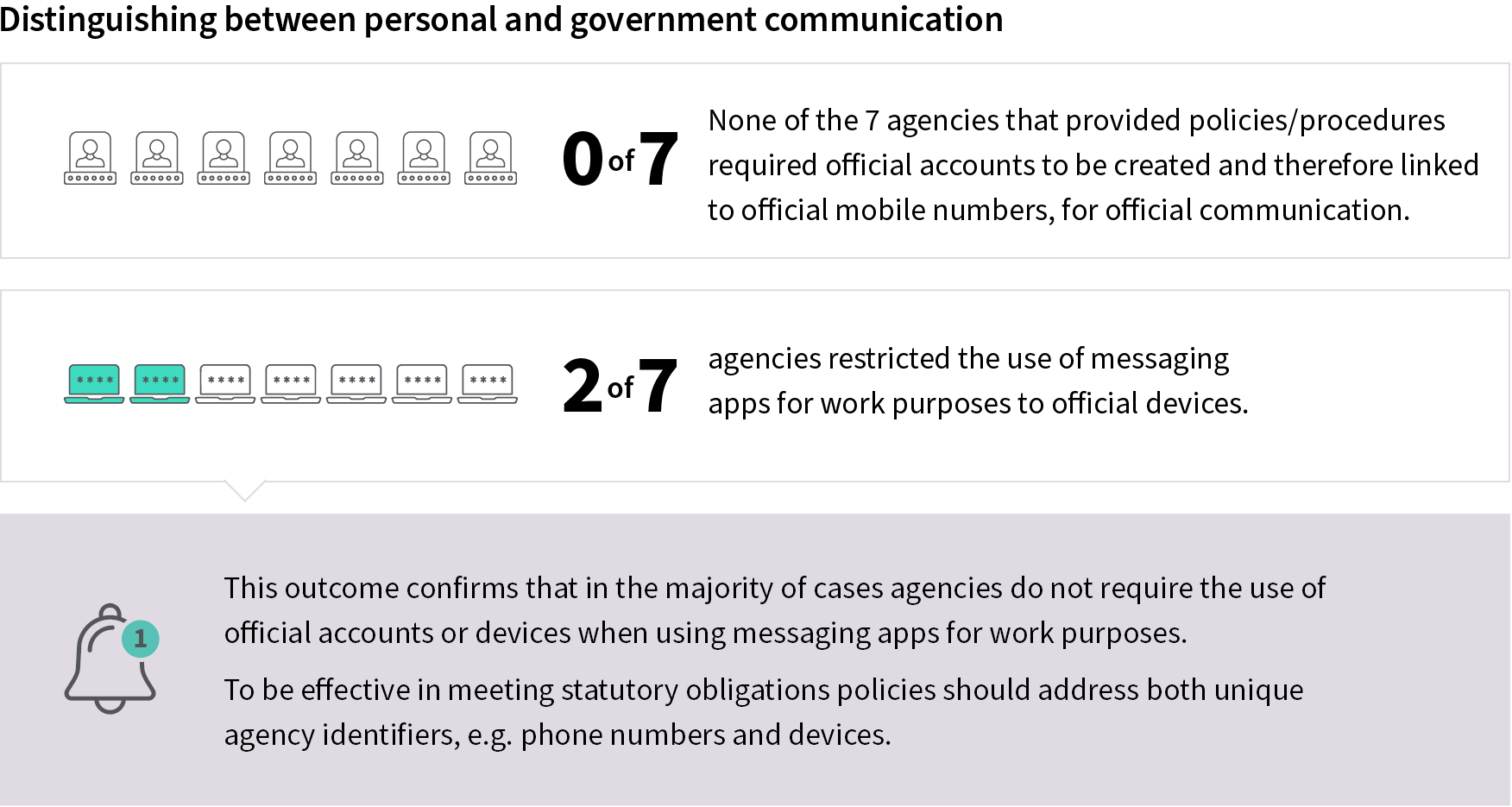

These policies generally did not address FOI, privacy and other key obligations. Of the 7 agencies that provided their policies or procedures:

did address essential security classification requirements

did not address essential archive requirements

did not adequately address FOI search requirements

did not require the use of official accounts or devices when using messaging apps for work purposes.

Recommendations

The report provides guidance to help agencies develop policies and procedures that ensure staff are able to meet FOI, privacy and recordkeeping requirements when using messaging apps.

Agencies should review existing policies or develop a policy to clearly set out whether or not they permit the use of messaging apps for work purposes.

Agencies that permit the use of messaging apps should have policies and procedures that adequately address information management, FOI, privacy and security considerations.

Agencies should examine the features of messaging apps needed to support official work. They should conduct appropriate due diligence on apps, consider the implications for communications with other agencies, and develop policies and procedures for individual apps.

Agencies that permit the use of messaging apps should conduct due diligence to ensure any preferred messaging app collects and handles personal information appropriately. This may be achieved through a privacy threshold assessment.

Foreword

Our digital environment demands a shift from a compartmentalised to a holistic approach to information governance by government agencies. No longer can we readily apply a linear interpretation to what constitutes: a ‘document’;[1] government information; a ‘record of an agency’;[2] or readily detach personal information from non-personal information. We must view our information governance obligations through the broadest lens and integrate the statutory safeguards that Parliament has determined to apply to what should be treated as a national resource to be managed for public purposes.[3]

As a public asset we must implement policies and practices to uphold these information governance safeguards. We must know:

- How are we managing information – directly within agencies or indirectly through outsourcing arrangements?[4]

- What information governance requirements apply?[5]

- How are we meeting those requirements?

- What information we are collecting and/or preserving?[6]

- Why are we collecting and/or preserving that information?

- How robust our systems and processes are in managing information governance requirements?

These are questions for all leaders including agency heads, oversight bodies and audit and risk committees. For many these are novel and complex questions in the context our digital environment. For all of us they are significant questions. As a regulator of information access and privacy rights they are of paramount concern to the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC).

Records must be created and maintained[7] to uphold these legislative requirements and the fundamental human rights of information access and privacy oversighted and promoted by the OAIC. Likewise, Australian Public Service (APS) values and the object of the Public Service Act 1999[8] remain immutable.

The purpose of this report is to examine the prevalence and application of messaging apps. Applying this fundamental knowledge, we can raise awareness of information governance obligations and contextualise those requirements within the parameters of the technology in use. Equipped with this knowledge we can provide effective regulatory guidance.

To be effective that guidance must reflect extant information governance obligations arising from the suite of statutes that safeguard government information and citizens’ rights. Accordingly, this report derives expert input from the Director General, National Archives of Australia (National Archives).

This co-regulatory approach is a first of its kind for the OAIC and National Archives. It has been a purpose driven and most productive engagement and one that will continue to deliver powerful results for government and the Australian community. As we work together through collaboration and regulatory initiatives such as these the OAIC and National Archives are better equipped to provide the holistic regulatory guidance required by agencies in this dynamic digital environment.

In addition to the expertise offered by National Archives this report would not have been possible without the engagement and support of Australian Government agency heads. The survey was voluntary and overwhelmingly agency heads responded positively and in accordance with the expressed timeframe. This commitment demonstrates a culture oriented toward voluntary compliance. That approach stimulates confidence and trust from regulators and the community.

The staff of the OAIC and National Archives have forged a productive working relationship through this regulatory initiative and importantly we have assimilated record creation, retention and disposal obligations with information access and privacy rights to provide a holistic approach to improving digital information governance. This report and the guidance provided is testimony to the benefits that can be achieved for both the regulated community and government. Most importantly this new approach provides significant benefits for each member of the Australian community in preserving their legislated rights and our precious system of representative democracy.

Elizabeth Tydd

Australian Information Commissioner

Message from National Archives of Australia Director-General Simon Froude

The findings of this report are a welcome contribution to our collective understanding of the extent to which messaging apps are used by Australian Government agencies, and the issues they face in managing these records. This information will help National Archives of Australia (National Archives) in developing advice and guidance for agencies about the management of these important Commonwealth records.

The dynamic and complex digital environment we live in today has seen rapidly evolving technologies blur the traditional definition of what is a record. It is more important than ever that information governance is at the forefront of our regulatory framework to counter disinformation and maintain public trust in government.

In this ever-changing world, National Archives continues to strive to meet its objective of improving information management maturity through the release of advice and guidance.

As part of this, National Archives built an information management framework based on the Information Management Standard for Australian Government and the Building Trust in the Public Record managing records, information and data for government and community policy.

Through the implementation of these, Australian Government agencies can improve how they create, capture, manage, use and reuse records, information and data created every day.

The call to improve Australian Government information governance is a consistent theme in the findings of royal commissions, audit reports and public inquiries. The Australian National Audit Office’s (ANAO) annual report for 23/24 noted that 'In the last five years, the ANAO has made negative comments on record keeping in over 90 per cent of performance audit reports presented to the Parliament. Of particular concern is that all 45 performance audit reports tabled in 2023–24 made negative comments on record keeping.'[9]

The results of the annual National Archives Check-up survey verify this finding which show that despite several years of sustained information management policy and guidance, information management maturity and performance has increased only slightly.

Records of government activity and decisions support democracy and increase government transparency and accountability. Inversely, poor information governance practices mean Australians do not have access to the records that tell our nation’s rich story. For a country whose history starts with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and continues with the stories of migrants from all over the world, records are a public asset of significant importance to the nation. Partnerships with agencies such as the Office of Australia Information Commissioner align with our purpose to provide leadership in best practice management of the official record of the Commonwealth.

I thank the Australian Information Commissioner for the opportunity to work with her office in bringing this report to fruition. As we look to the future, National Archives will continue to improve access to government information to ensure that our shared national record can be trusted for generations to come.

Simon Froude

Director General

National Archives of Australia

Introduction

Accountability and transparency are essential for good government. They are enabled by good recordkeeping and a strong FOI system.

Accountability relies on information – such as decisions of government, and the evidence and advice on which those decisions are based – being appropriately recorded and managed. These records must be securely retained in an accessible manner for as long as required to meet ongoing business needs and legal requirements.

Under the Archives Act, National Archives is responsible for overseeing Commonwealth recordkeeping, by determining standards and providing advice on information management to Australian Government agencies, and authorising disposal of Commonwealth records.[10]

The FOI Act sets out the public’s right to access documents held by government.[11] The OAIC oversees the operation of the FOI Act and reviews decisions made under it by agencies and ministers.

The FOI system makes transparency the government’s default position; it ensures agencies[12] provide access to government information with limited exceptions, rather than maintaining secrecy with limited public access to information. FOI supports better-informed decision-making by increasing public participation in government processes. FOI also enables increased scrutiny and review of government decisions.[13] Further, FOI is a key mechanism to enable people to know what information government holds about them.

The Privacy Act deals with how agencies and organisations handle personal information. The Privacy Act is another key mechanism to enable people to know what information government holds about them.[14] It requires Australian Government agencies to ensure the personal information they handle is collected, held, used and disclosed within a robust legal framework.

Together, the obligations under the Archives Act, FOI Act and Privacy Act ensure that the government both records information appropriately and provides public access to that information.

Increasing use of messaging apps

Parliament has legislated to safeguard government information. When the FOI Act and Archives Acts commenced (in 1982 and 1983 respectively),[15] agencies principally used paper-based files. Australia’s first mobile phone system had only just been launched, with car phones weighing 14 kilograms and offering 20 minutes talk time.[16]

The subsequent 4 decades have seen dramatic advances in information communication technologies, with exponential growth in the amount of data government generates and major changes in communication practices.

Since around 2010, phone-based instant messaging apps have emerged as popular forms of communication. These apps offer security, encryption, convenience and accessibility so may be seen as providing significant benefits for government officials.[17]

But while these apps facilitate instant and secure communication over vast distances, they present novel considerations for recordkeeping, FOI and privacy. Unlike more mainstream forms of professional communication such as email, the information from these apps is not hosted on government servers. Officials might communicate through accounts created in their personal capacity, possibly on personal devices, rather than their official capacity on government-owned devices. Many of these apps have the ability for users to send messages that can irretrievably disappear after a pre‑determined period,[18] potentially resulting in unlawful destruction of information under the Archives Act.

What are messaging apps?

In this report, when we refer to messaging apps, we are looking at mobile-based consumer messaging applications, such as Signal, WhatsApp, Telegraph and Facebook messenger. A common function of these messaging apps is the ability to send messages that disappear (are automatically destroyed) after a specified period.

This report does not look at enterprise-level messaging systems, such as Microsoft Teams or Webex. Typically, these accounts are agency-hosted and messages that have been sent do not automatically disappear. We also do not look at short message service (SMS, better known as text messages) as their use has been commonplace for over 2 decades, are traditionally linked to devices (rather than accounts) and do not offer the same features as messaging apps like encryption or disappearing functionality.

Recordkeeping, privacy and FOI when using messaging apps

Information created or received by officials constitutes Commonwealth records for the purposes of the Archives Act,[19] and needs to be handled in accordance with National Archives’ standards and guidance. This extends to official information sent or received via messaging apps, including disappearing messages.[20]

Rights of access to personal information held by organisations including government are enshrined under the Privacy Act.[21] Likewise access to government records and obligations including those that secure access even in outsourced service delivery[22] search and retrieval, providing assistance to applicants, timely decision‑making and proactive release of prescribed information together with proactive release of information are all governed under the FOI Act. These obligations must be supported through information governance policies and procedures that reflect our digital environment. Messaging apps are an established a feature of the digital government environment.

In the context of digital government agencies’ information holdings are increasing exponentially and that situation demands a focus on record creation and keeping.

While all information sent or received by people in an official capacity are Commonwealth records, not all records will necessarily need to be captured and retained in an agency’s recordkeeping system. For records that agencies need to keep, they must be retained as long as required to meet minimum retention periods stipulated in relevant records authorities issued by National Archives.[23] This includes agency-specific authorities and general records authorities. Failure to adequately identify, capture and retain messages communicated via apps (including disappearing messages) that are created or received by agency staff in connection with the conduct of agency business, may breach the Archives Act and be considered unlawful destruction of a Commonwealth record.[24]

Under the FOI Act every person has a legally enforceable right to obtain access to documents of an agency or official document of a minister, other than exempt documents. For the purposes of FOI, the definition of ‘document’ includes electronically stored information.[25]

In late 2024 the OAIC asked 25 agencies to complete a questionnaire to better understand Australian Government agency information governance practices and policies in the context of messaging apps. Twenty-two of the 25 agencies responded. Appendix A has more information about our methodology.

Part 1: Agency use of messaging apps

Do agencies permit the use of messaging apps?

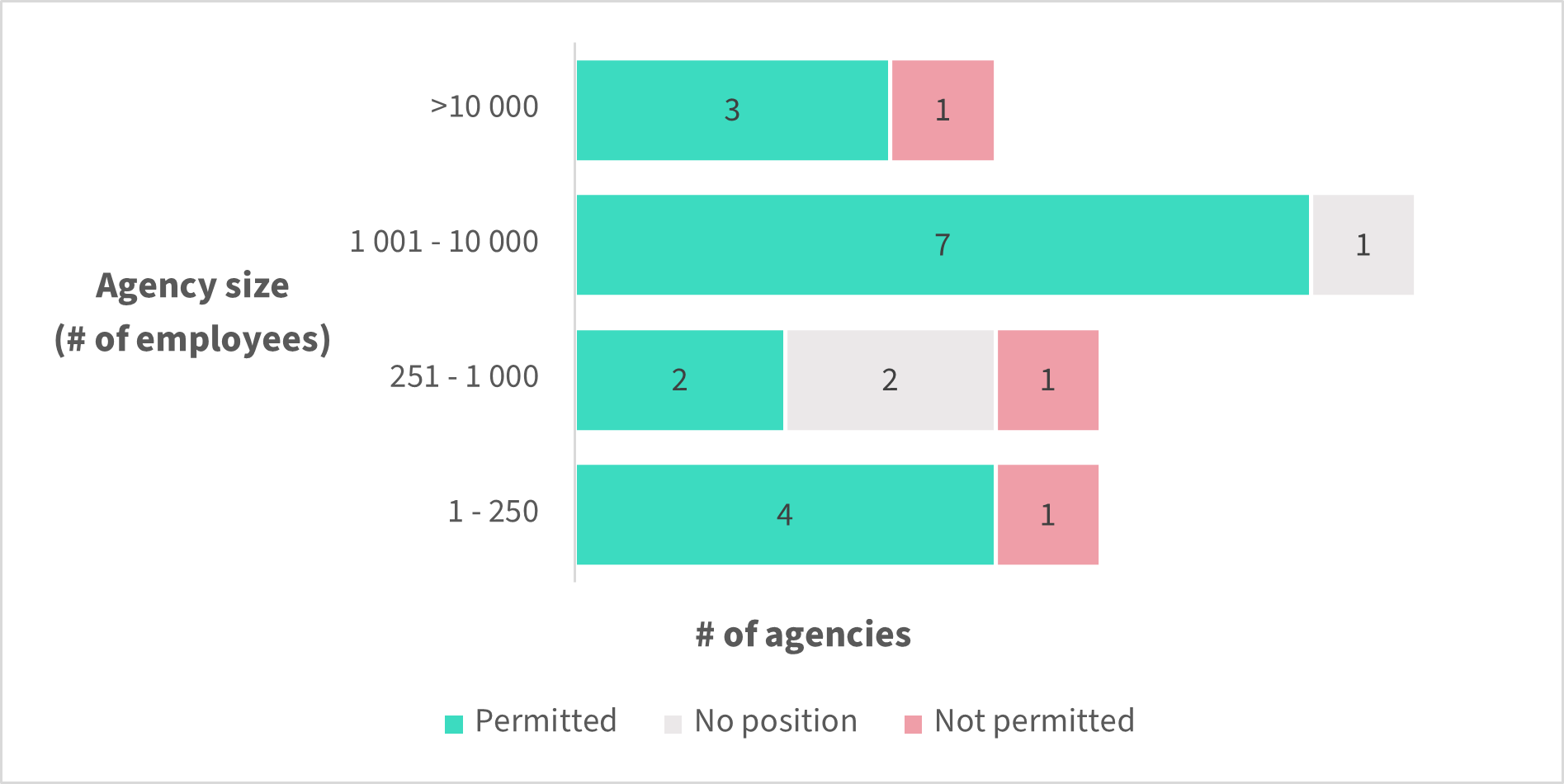

Of the 22 respondent agencies

- 73% expressly permitted the use of messaging apps for work purposes

- 14% expressly prohibited the use of messaging apps for work purposes

- 14% did not have a position about their use.

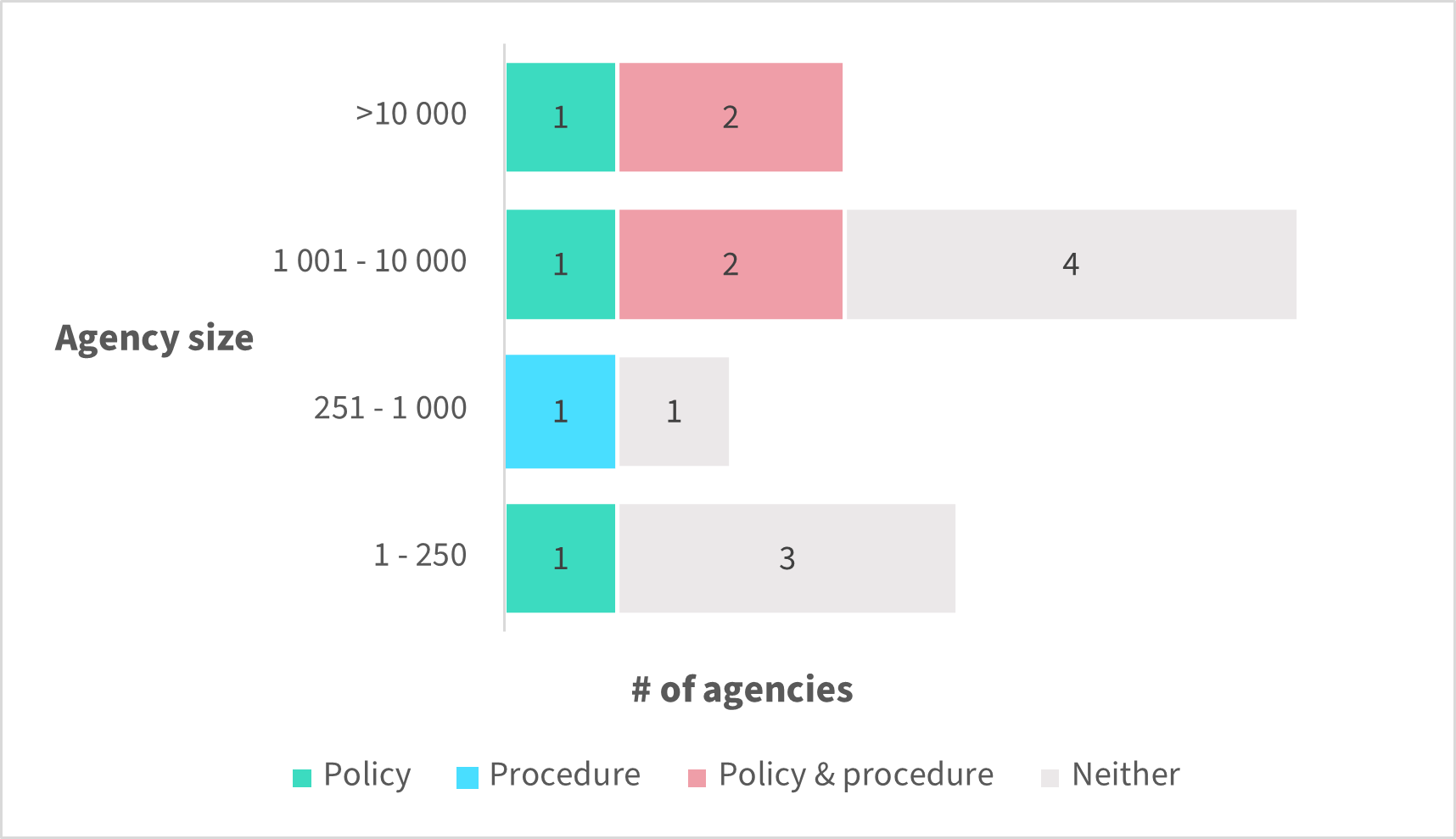

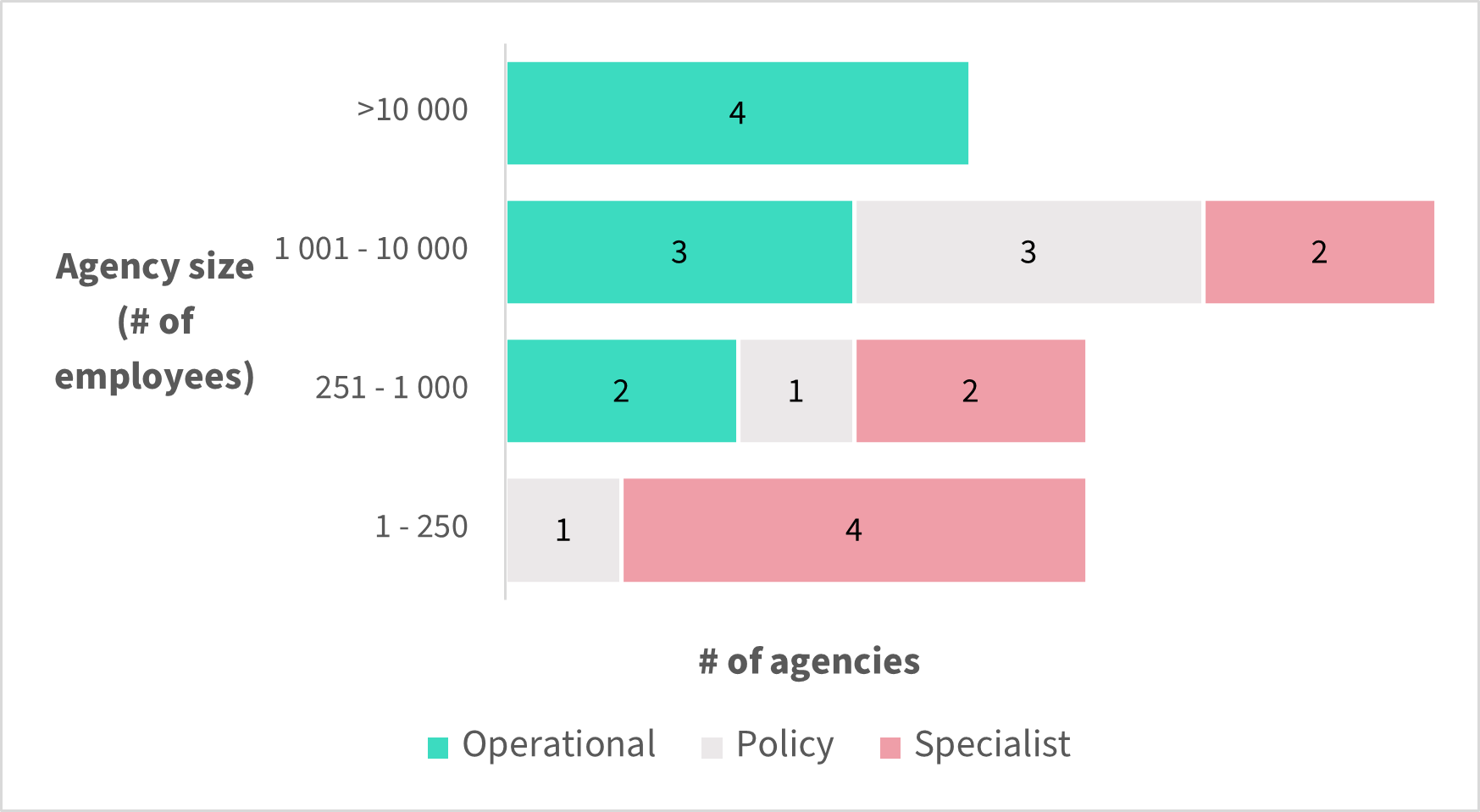

Figure 1 shows that messaging apps are permitted for work purposes by the majority of agencies in 3 of the 4 agency size categories. Three of the 4 very large agencies permitted messaging apps, one expressly prohibited their use. Seven large agencies permitted their use, one had no position. Four of the 5 small agencies permitted their use, one prohibited it.

The exception was medium size agencies, where their approach was more mixed. Of the 5 medium sized agencies, 2 permitted the use of messaging apps for work purposes, one prohibited their use and 2 had no position on their use.

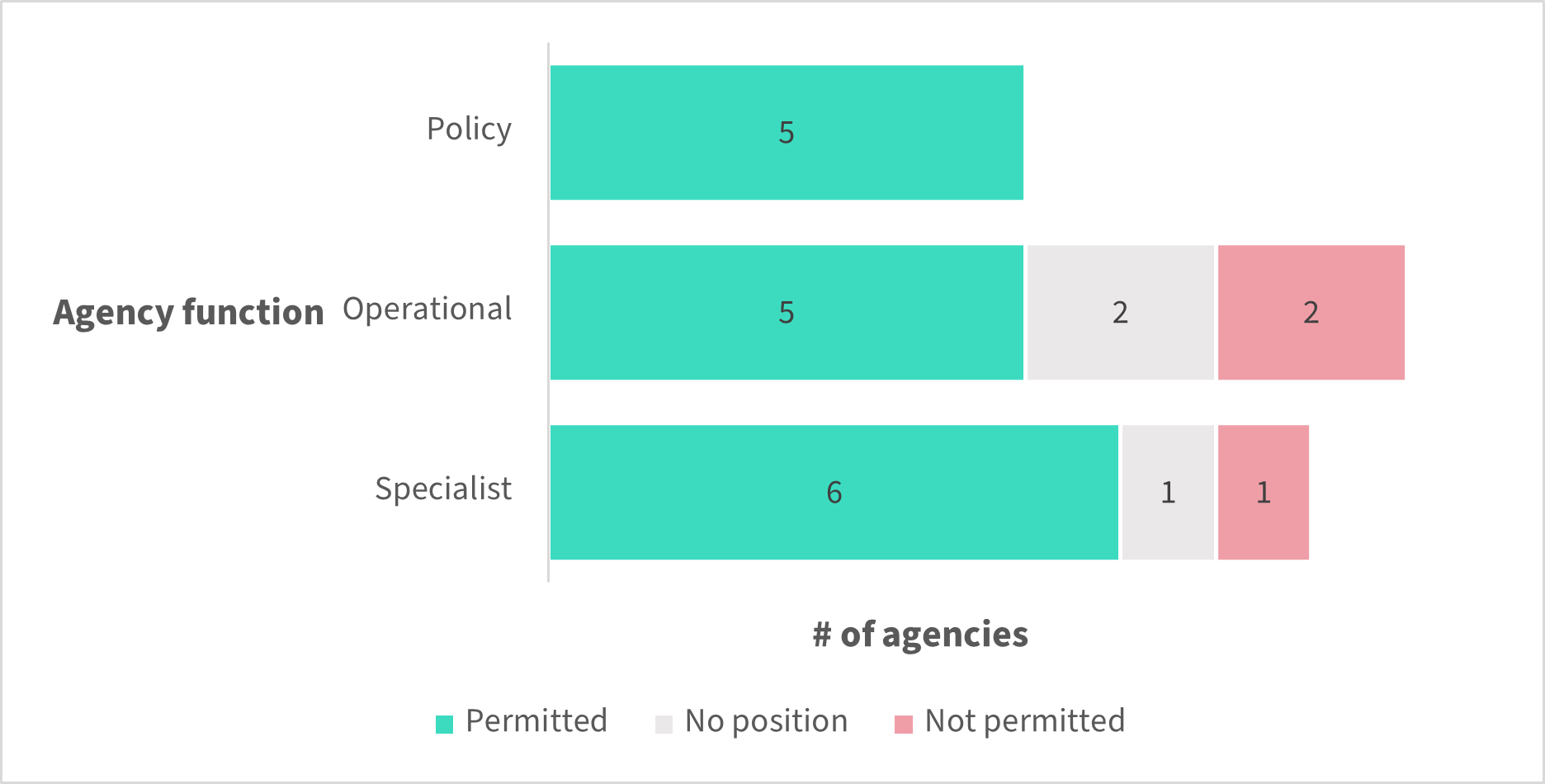

Figure 2 shows that when grouped by agency function, for each function the majority of agencies permitted the use of messaging apps. All policy agencies that provided responses expressly permitted staff to use messaging apps for work purposes. Six of the 8 specialist agencies permitted messaging apps, one prohibited their use for work purposes and one did not have a position on their use.

There was the greatest variance for the 9 operational agencies. While 5 permitted the use of messaging apps, 2 prohibited them and 2 had no position.

Of the 3 agencies that did not have a position on the use of messaging apps for work purposes:

- 2 agencies planned to permit the use of messaging apps in the future

- 1 did not have any plans to permit the use of messaging apps.

Are agency staff likely to be using messaging apps?

Where agencies permitted the use of messaging apps for work purposes, or had no position on their use, we asked the respondent how likely it was that agency staff were using them.[26]

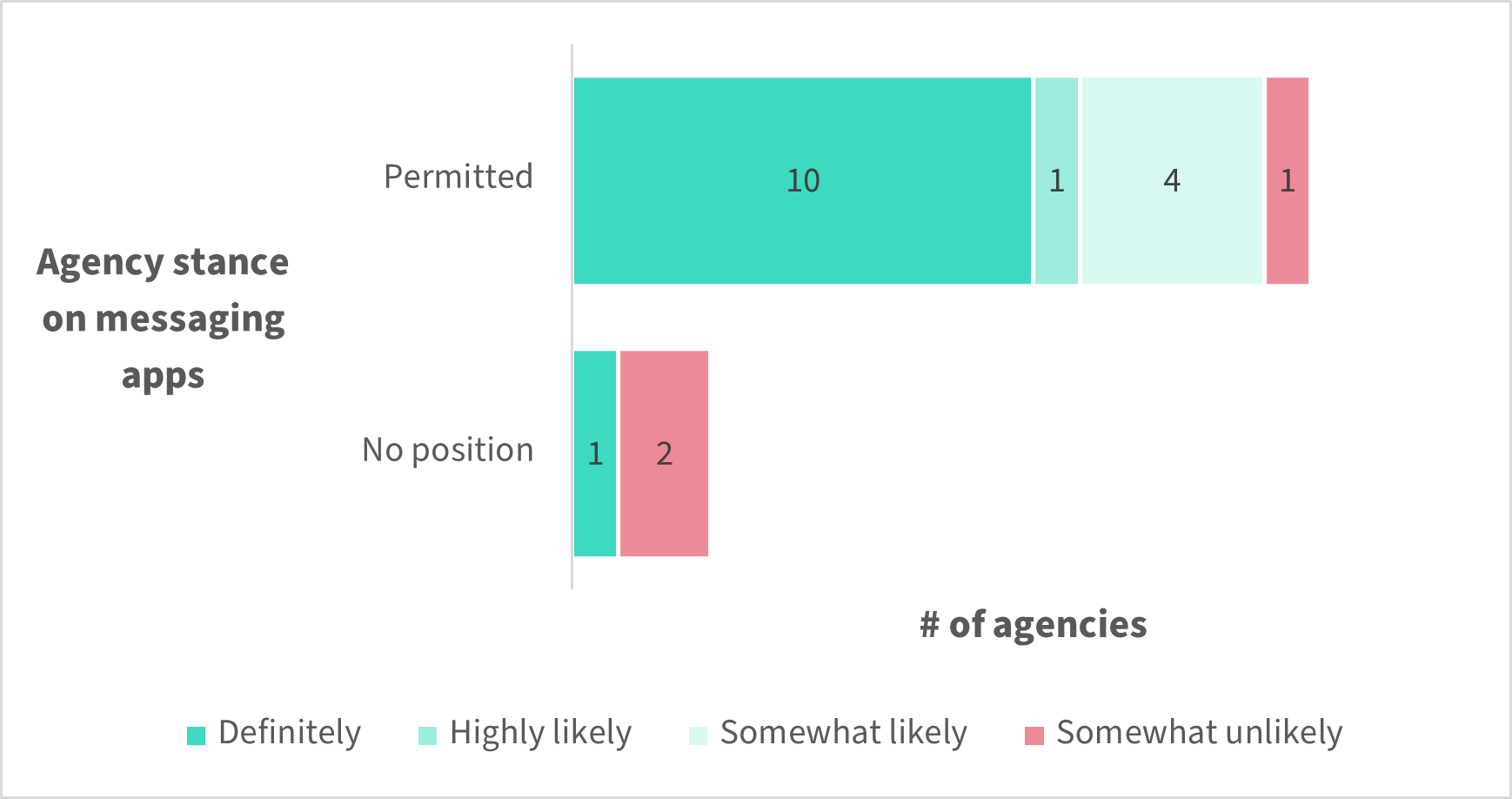

Figure 3 shows that for agencies that permitted the use of messaging apps, in the experience of 10 of the officers who responded, agency staff were definitely using messaging apps for work purposes. Five of the officers thought it was highly likely or somewhat likely staff were using messaging apps. One thought it was unlikely staff were using messaging apps.

Conversely, for agencies that do not have a position on the use of messaging apps, two officers thought it was unlikely staff were using messaging apps. However one officer responded that staff were definitely using the apps for work purposes.

What messaging apps are agencies using?

Of 16 respondent agencies that expressly permitted the use of messaging apps for work purposes

- 69% endorsed, encouraged or preferred one, which was Signal

- 6% endorsed, encouraged or preferred both Signal and WhatsApp

- 25% did not endorse, encourage or prefer any app.

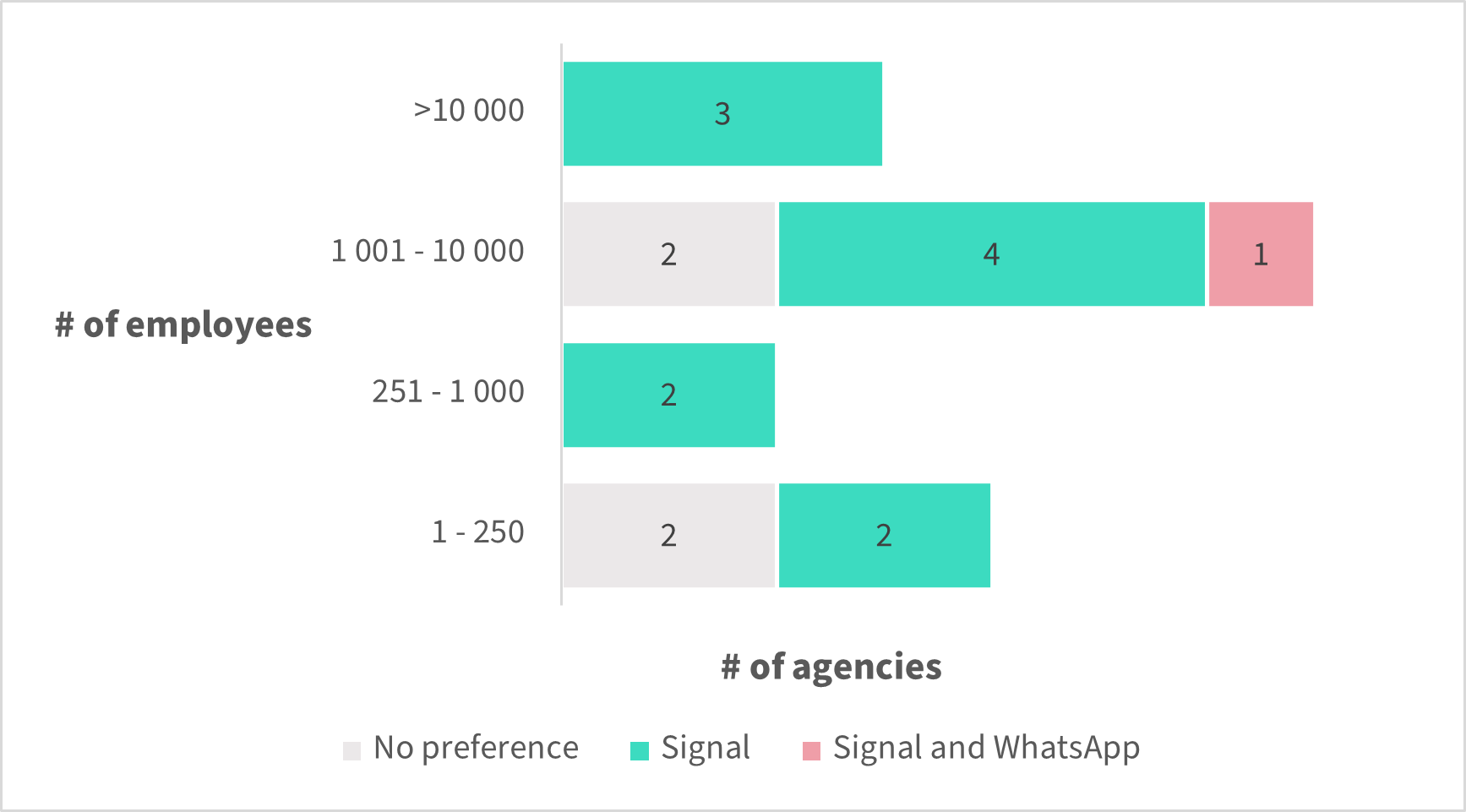

Figure 4 shows the breakdown by agency size. All of the 3 very large agencies that permit the use of messaging apps prefer Signal. While 2 large agencies do not have a preference, 4 prefer Signal and one prefers both Signal and WhatsApp. Both medium sized agencies that permit messaging apps prefer Signal.

Notably, half (2) of the small agencies that permit the use of messaging apps do not have a preference. The other 2 agencies prefer Signal.

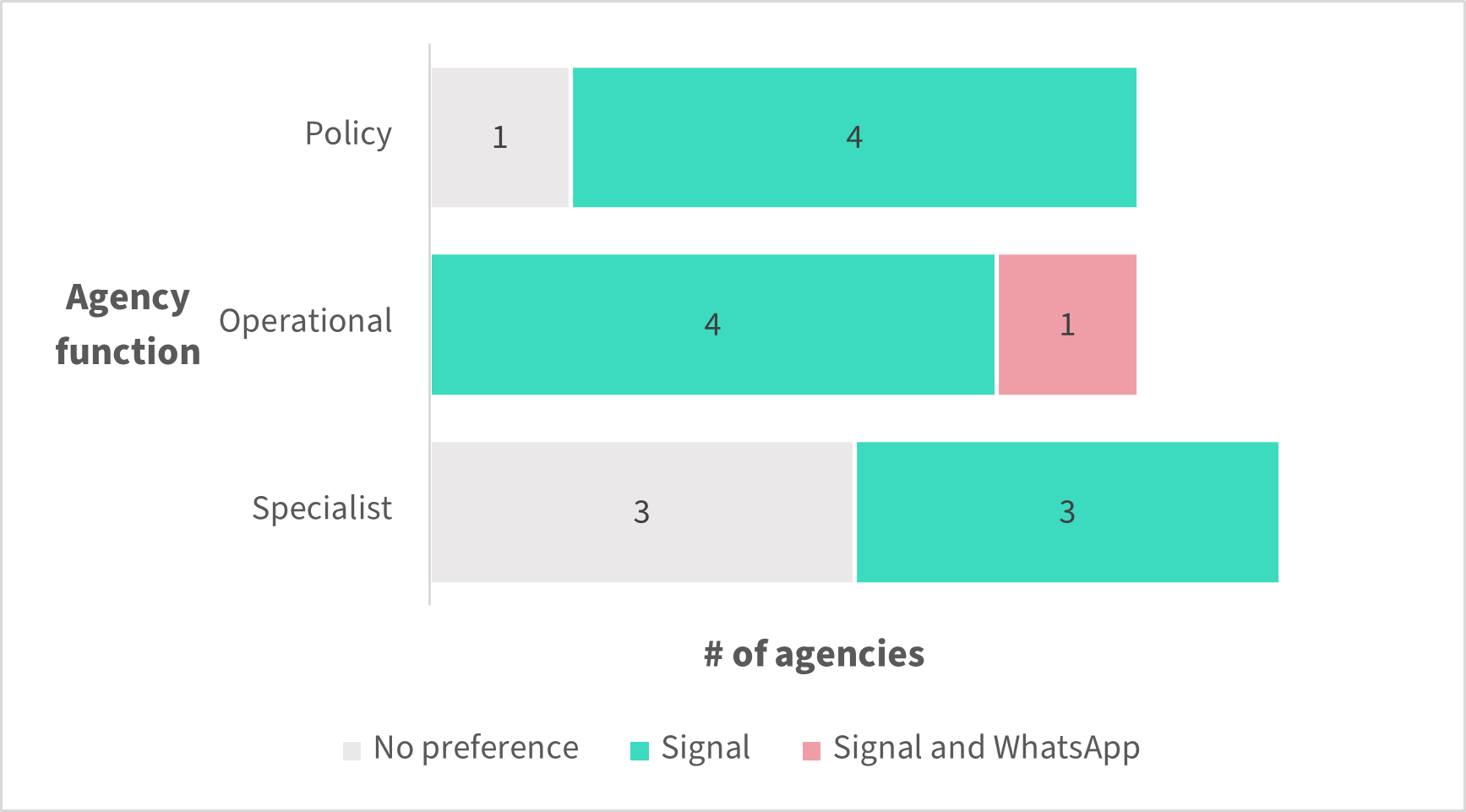

Figure 5 shows policy and operational agencies that permit the use of messaging apps for work purposes have a strong preference for Signal. All 5 operational agencies endorse, encourage or prefer Signal (one also endorses, encourages or prefers WhatsApp) and 4 of the 5 policy agencies endorse, encourage or prefer Signal (one does not have a preference).

The result is notably different for specialist agencies, half (3) endorse, encourage or prefer Signal and the remaining half (3) do not have a preference.

Do agencies that permit messaging apps have policies or procedures about their use?

Of the 16 agencies that permit the use of messaging apps for work purposes, 8 (50%) have policies and/or procedures about their use by staff. The 3 agencies that prohibit the use of messaging apps for work purposes have policies doing so. The 3 agencies that do not have a position on the use of messaging apps do not have policies.

Of the 8 agencies that did not have policies and/or procedures about the use of messaging apps, 2 planned to develop a policy and/or procedure. 5 did not and one responded that it was unsure.

For agencies that permit the use of messaging apps, figure 6 shows some correlation between whether or not agencies have policies with the size of agency.

All very large agencies that permit the use of messaging apps have policies, and 2 also have procedures. A little under half (3) of the 7 large agencies that permit the use of messaging apps have policies, and 2 of these 3 also have procedures. One of the 2 medium size agencies has procedures for the use of messaging apps. Only one of the 4 small agencies that permit the use of messaging apps has a policy or procedure.

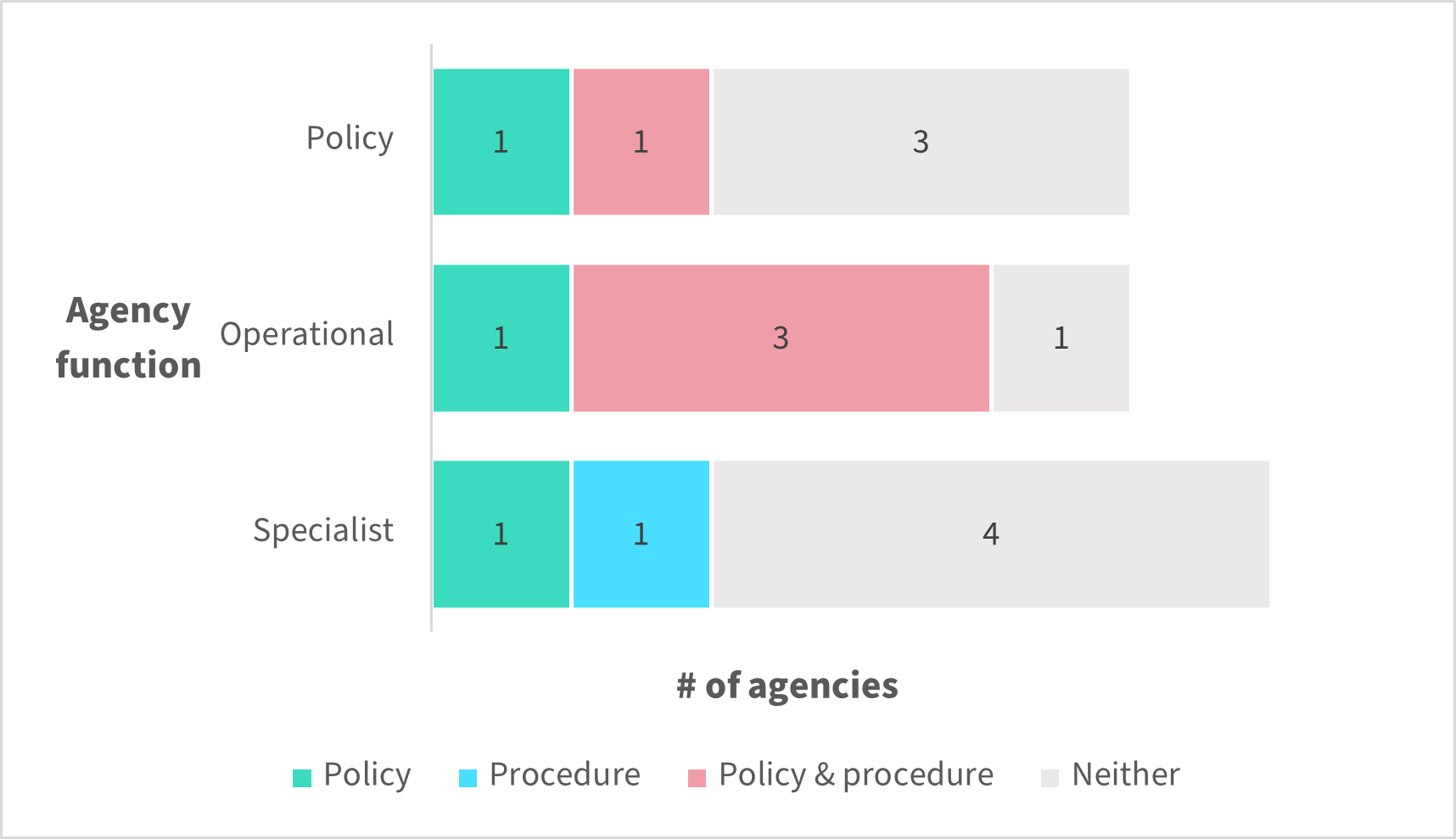

Figure 7 shows that almost all (4) of the 5 operational agencies that permitted the use of messaging apps had policies on their use, and 3 also had procedures. This is considerably different to policy agencies and specialist agencies.

Two of the five policy agencies that permit the use of messaging apps have policies about their use, one of these 2 also has procedures. Of the 6 specialist agencies that permit the use of messaging apps, one had a policy and another had a procedure about use of the apps.

All agencies that had policies and/or procedures about the use of messaging apps communicated those policies and/or procedures via their intranet. In addition, one emailed the policy to new staff, another sent email reminders annually, and a third sent reminders via internal communications bulletins. A fourth agency included the policy on messaging apps in mandatory induction training.

For agencies that did have policies and/or procedures in place regarding the use of messaging apps, we asked whether they allowed or required specific categories of staff to use messaging apps for work purposes. None of the agencies differentiated access to messaging apps for work purposes by specific categories of staff.

Significantly, while 12 agencies had a messaging app they encouraged, endorsed or preferred, only 8 (67%) had policies and/or procedures about their use. We did not ask agencies how they communicated their preferred messaging app to staff.

Do agencies use messaging apps to convey personal information?

We asked the 16 agencies that permitted the use of messaging apps for work purposes, and the 3 agencies that didn’t have a position about their use, whether messaging apps were used to convey personal information about members of the public. Of these 16 agencies:

- 68% were confident messaging apps weren’t used to convey personal information about members of the public.

- 32% weren’t sure.

The varied approaches to use of personal devices and the limited guidance and/or absence of procedures and policies that address information governance requirements introduces a significant risk to the preservation of information access and privacy rights.

In the absence of sound policies and guidance APS employees operate without the tools necessary to uphold their responsibilities and agencies are not able to monitor compliance and confidently secure fundamental rights. In some instances, privacy rights are secured by the deletion of personal information. This dimension should also be considered by agencies in their policies and practices.

This report examines the adequacy of the policies and practices in Part 2.

Part 2: What are agencies’ policies and practices regarding the use of messaging apps?

In addition to completing a questionnaire, we asked agencies to share their policies and procedures related to their use of messaging apps for work purposes. Of the 8 agencies that advised they have policies and/or procedures relating to the use of messaging apps (see Figure 6), 7 (87%) provided relevant policies and/or procedures. This chapter highlights some similarities and differences in these policies and procedures.

Policies and procedures should reflect legislated rights and extant legislated or APS policy obligations. In summary these policies/procedures should contain information to secure:

- record creation and retention requirements – archive requirements[27]

- security and classification requirements[28]

- FOI obligations[29]

- privacy obligations.[30]

Six agencies’ policies and/or procedures directly reference messaging apps and distinguish the standards applicable to the use of these services. The other agency’s policy related to storing information more generally. It grouped messaging apps with email and social media, and addressed ICT security as it relates to device use.

The 3 agencies that prohibit the use of messaging apps have policies to this effect. We have not reviewed their policies in this chapter.

Do policies address archiving requirements?

Under the Archives Act, agencies are responsible for identifying, capturing and retaining Commonwealth records that are required to provide evidence of business activities and decisions. They must then determine how to retain official records in a manner that preserves their authenticity, reliability, integrity and useability.

National Archives requires agencies to determine the value of Commonwealth records by assessing their overall significance based on their purpose and content, and any ongoing business needs or legal requirements to retain the records[31] – including identifying minimum retention requirements for these records in applicable National Archives’ issued records authorities.[32]

All 7 policies and/or procedures we reviewed addressed the need to retain information in accordance with the Archives Act. Only one agency advised how messages are to be extracted from the app to its recordkeeping system, stating that a screenshot may be a means of extracting this information.

Do policies address the security classification of the information staff can communicate via messaging apps?

The Australian Government Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) requires agencies that generate information to assess the value, importance or sensitivity of the information. They do this by considering the potential damage that would arise if the information’s confidentiality was compromised. They must assign the corresponding protective marking or security classification to that information. That information can only be handled and communicated using networks with the minimum levels of protection required for the information’s security classification.

Five (71%) agencies of the 7 that provided policies (31% of agencies that permit the use of messaging apps) addressed the classification that messaging apps were able to handle. One agency’s policy addressed the use of distribution limiting markers more generally but did not specify how these relate to messaging apps.

Of the 5 agencies that addressed classification in their policies and/or procedures, all encouraged, endorsed or preferred Signal. Two of these agencies allowed the use of Signal for materials classified as PROTECTED and below. Two allowed the use of Signal for materials classified OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE and below. One agency allowed the use of Signal for documents classified as OFFICIAL and below.

Do policies address the need to search apps for FOI purposes?

Only 2 agencies’ policies and/or procedures addressed the need for staff to search messaging apps in response to FOI applications. This represents 13% of agencies that permit the use of messaging apps for work purposes.

Do policies consider the disappearing messaging function of messaging apps?

Two (28%) agencies of the 7 that provided policies (13% of agencies that permit the use of messaging apps) addressed the disappearing messages functionality of these apps, prohibiting its use. One of these provided instructions to turn off this function. The failure to preserve information may result in a failure to comply with Archives Act requirements and preclude the operation of the FOI Act.

Do policies require separate work accounts for messaging apps?

Some messaging apps, including Signal and WhatsApp, use phone numbers as the unique identifying information to create an account.

Complying with recordkeeping, FOI and privacy obligations can become more difficult for staff, and to present compliance challenges for agencies, if staff use an account created for personal communication for the purpose of official communication. In practice this means that staff use a personal or non-official phone number as the unique identifying information.

Accordingly, we reviewed agencies’ policies and procedures to identify what steps they took to distinguish between accounts created using an agency-linked unique identifier (such as phone number) and accounts created using personal identifiers.

Of the 7 agencies’ policies and/or procedures we reviewed, no agencies required an official phone number to be used to create an official account, and no agency required a separate, official account to be used in order to communicate official information. However, 2 agencies stated that messaging apps could only be used for work purposes on work devices. This requirement has the practical effect of using only an official identifier and therefore excludes the use of personal phone numbers as a unique identifier. One of these 2 agencies permits only messages to be sent to recipients using mobiles issued by the same agency.

To be effective in meeting statutory obligations policies should address both unique agency identifiers, e.g. phone numbers and devices.

Good practice case study

Of the policies and/or procedures we reviewed, the most comprehensive set of documents was from a very large agency. This agency provided 7 documents of policies and procedures relating to the use of messaging apps. These documents addressed:

- record creation and retention requirements – archive requirements

- security and classification requirements

- requirements for official devices to be used

- FOI obligations

- privacy obligations (although not specifically in the context of messaging apps).

This agency endorsed the use of Signal, citing the app’s security. It stated Signal was only for use on mobile devices managed by the agency.

The agency provided cyber security guidelines for the use of Signal as well as a task card for how the app should be configured. The task card described how the disappearing messaging functionality should be switched off. Further, this agency provided guidance about keeping records in its storing corporate information guide and cyber security FAQs.

To further ensure it meets its obligations under the FOI Act, Privacy Act and Archives Act, this agency should strengthen its policies to include:

- specific instructions about how to copy information from Signal to its primary recordkeeping system

- searching messages in Signal for FOI purposes

- specific instructions regarding the use of the personal information of others in Signal.

The agency could consider including requirements to link Signal accounts to an agency‑controlled identifier (such as the phone number of the agency-issued mobile).

Part 3: Findings and recommendations

Based on the analysis in chapters 2 and 3, this chapter identifies findings about Australian government agencies’ use of messaging apps and makes recommendations to address those findings. We will revisit this topic in 2 years (2027) to understand how use of messaging apps in the APS has evolved.

These findings and recommendations are directed to preserve rights by assisting agencies to more readily comply with their information management, FOI and privacy obligations. As agencies which promote access to information, we note our role in supporting agencies mature their approach to managing information in messaging apps.

The OAIC will work with National Archives to support the agencies to understand their recordkeeping, FOI and privacy obligations.

The OAIC will:

- Work with National Archives to support the agencies to understand their recordkeeping, FOI and privacy obligations.

- Revisit this topic in 2 years (2027) to understand how use of messaging apps in the APS has evolved

Recommendations for agencies

- Agencies should review existing policies or develop a policy to clearly set out whether or not they permit the use of messaging apps for work purposes.

- Agencies that permit the use of messaging apps for work purposes should have policies and/or procedures about the use of those apps that address information management, FOI, privacy and security considerations that:

- adequately address FOI requirements, including those relevant to accessing records under the FOI Act, and recordkeeping obligations under the Archives Act

- explain how to extract information from messaging apps, either in response to an FOI request or to store on recordkeeping systems

- address whether accounts created for official purposes, using phone numbers linked to agency-issued phones, are required to communicate official information

- adequately address privacy requirements including those relevant to accessing and amending records under the Privacy Act

- address the security classification of information that messaging apps can handle

- explain when the disappearing message functionality must be turned off, and how to do so

- confirm whether staff are permitted to use messaging apps to communicate the personal information of members of the public.

- Agencies should examine the features of messaging apps necessary to support official work. They should conduct appropriate due diligence on apps, consider the implications for communications with other agencies, and develop policies and procedures specific to individual apps.

- Agencies that permit the use of messaging apps should conduct due diligence to ensure any preferred messaging apps collects and handles personal information appropriately, this may be achieved through a privacy threshold assessment.

Finding 1: Use of messaging apps is widespread in government agencies

Of the 22 agencies that responded to our questions, 16 agencies (73%) permitted the use of messaging apps for work purposes. However, only 3 (14%) had policies prohibiting their use.

Three (14%) had no position on their use. Of the 3 agencies that had no position on their use, 2 respondents speculated it was unlikely messaging apps were being used for work purposes but one respondent thought they definitely were.

Based on these results it is reasonable to infer that the use of messaging apps is widespread across Australian Government agencies.

Unless agencies have a policy of specifically prohibiting the use of messaging apps, they should consider there is a reasonable likelihood that their staff are using messaging apps for work purposes.

Finding 2: Policies and procedures to guide the use of messaging apps require review and revision to meet legislative obligations

Information generated or communicated in messaging apps – in people’s capacity as Australian Government officials – is subject to the Archives Act, the Privacy Act, the FOI Act and security classification requirements, just like other communications methods. However, messaging apps present novel considerations that can complicate compliance with these statutes.

Eight (50%) of the 16 agencies that permitted the use of messaging apps did not have policies and/procedures regarding the use of messaging apps for work purposes. Of the 7 agencies that provided relevant policies/procedures:

- 1 (14%) agency provided policies/procedures addressing essential archiving requirements

- 5 (71%) agencies provided policies/procedures addressing essential security classification requirements

- 5 (71%) agencies provided policies/procedures including some guidance to distinguish between personal communication and government communication

- 2 (28%) agencies provided policies/procedures addressing essential FOI search requirements

- 2 (28%) agencies provided policies/procedures addressing essential FOI and archiving requirements relevant to disappearing messaging functionality.

To navigate the novel considerations that arise from the use of messaging apps and ensure that they are able to uphold legislative obligations and the legislated rights of the community, agency staff require policies and procedures that are specific to messaging apps.

- adequately address FOI requirements, including those relevant to accessing records under the FOI Act, and recordkeeping obligations under the Archives Act

- explain how to extract information from messaging apps, either in response to an FOI request or to store on recordkeeping systems

- address whether accounts created for official purposes, using phone numbers linked to agency-issued phones, are required to communicate official information

- adequately address privacy requirements including those relevant to accessing and amending records under the Privacy Act

- address the security classification of information that messaging apps can handle

- explain when the disappearing messaging functionality must be turned off, and how to do so

- confirm whether staff are permitted to use messaging apps to communicate the personal information of members of the public.

Finding 3: There may be benefits to agencies using one messaging app across the agency

Eleven (69%) of the 16 agencies that permit the use of messaging apps for work purposes, endorsed, encouraged or preferred the use of one app. (One agency endorsed, encouraged or preferred 2 apps.)

There are likely to be benefits to agencies only allowing the use of one messaging app across the agency. Only allowing one app means:

- all staff are working off one platform, meaning they do not need to create accounts across multiple apps to communicate with colleagues, or track communications across multiple apps

- agencies would only need to do due diligence on one app (to ensure that app offered appropriate security and privacy protections)

- agencies would only need to create procedures for one app to instruct staff how to conduct FOI searches, transfer records onto official agency records systems, or turn off the app’s disappearing message capabilities.

If agencies allow staff to communicate with staff in other agencies, there are ‘network effects’ where it may become attractive for agencies to converge to the same app. We note it is critical for agencies to do their own due diligence on apps to satisfy themselves they meet the necessary privacy and security requirements.

Finding 4: Agencies’ use of messaging apps may adversely impact their ability to uphold their privacy, FOI and recordkeeping obligations

This report found that 6 (32%) of the agencies that permitted the use of messaging apps, or had no position on their use, were unsure whether staff were using messaging apps to convey personal information about members of the public.

If an agency permits the use of messaging apps for work purposes, the agency has obligations to ensure the app handles personal information appropriately.

If agency staff are using (or even possibly using) messaging apps to convey personal information, agencies are required to ensure this information is being collected, held, disclosed and destroyed[33] appropriately. As well as being made available in response to FOI applications, and kept as records in line with archival obligations, that information must be able to be corrected or annotated consistent with the FOI Act,[34] and accessed and corrected (or have a statement associated) consistent with the Privacy Act.[35] This is particularly important if personal information relates to a decision being made in relation to that person.

Part 4: Appendices

Appendix A: Methodology

On 22 November 2024, the Information Commissioner wrote to the heads of 25 Australian Government agencies [36] asking the agencies to complete a questionnaire about their use of messaging apps. The Information Commissioner requested completion by an officer with senior operational responsibility for the agency’s information management.

We approached a broad cross-section of agencies to understand if and how these agencies were using messaging apps, and what if any policies or procedures they had in place to guide staff when they used those apps for official business.

Between 25 November and 23 December 2024, 22 agencies provided responses to the questions. By size, there were 4 very large agencies (more than 10 000 staff), 8 large agencies (1 001 to 10 000 staff), 5 medium agencies (251 to 1 000 staff) and 5 small agencies (250 staff or fewer). By function there were 9 operational agencies, 8 specialist agencies and 5 policy agencies.[37]

The 4 very large agencies were exclusively operational, and the 5 small agencies were mainly specialist agencies. The 8 large agencies and 5 medium agencies were more diverse. Figures 8 gives an overview of the respondent agencies, showing them by number of employees and functional cluster. We applied functional clusters according to the APSC’s 2022-23 State of the Service Report. Table 1 outlines the agencies and provides their size and functional cluster.

OAIC staff analysed the agencies’ responses. Where there was a large enough response rate we disaggregated by size of agency and functional group. We note some groupings were correlated:

- 3 of the 5 policy agencies were large agencies

- 4 of the 5 small agencies were specialist agencies (half of the specialist agencies)

- all of the very large agencies were operational agencies (4 of the 9 operational agencies).

Agency name | Size | Functional cluster |

|---|---|---|

Australian Research Council | Small | Specialist |

Administrative Review Tribunal | Medium | Operational |

Australian Digital Health Agency | Medium | Specialist |

Australian Federal Police | Large | Operational |

Australian Law Reform Commission | Small | Policy |

Australian Public Service Commission | Medium | Policy |

Australian Taxation Office | Very large | Operational |

Australian Trade and Investment Commission | Large | Specialist |

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation | Large | Specialist |

Department of Defence | Very large | Operational |

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade | Large | Policy |

Department of Home Affairs | Very large | Operational |

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet | Large | Policy |

Department of Veterans’ Affairs | Large | Operational |

Digital Transformation Agency | Medium | Operational |

Independent Parliamentary Expenses Authority | Small | Specialist |

National Anti-Corruption Commission | Small | Specialist |

National Disability Insurance Agency | Large | Operational |

National Health and Medical Research Council | Small | Specialist |

National Indigenous Australians Agency | Large | Policy |

Office of the Commonwealth Ombudsman | Medium | Specialist |

Services Australia | Very large | Operational |

As part of the questionnaire, we asked agencies that had policies and procedures relating to their use of messaging apps to send those policies and procedures to the OAIC. This included not only policies and procedures directly related to messaging apps, but also broader policies and procedures that included reference to messaging apps.

We received policies and procedures from 8 agencies. As the response from one agency was general in nature and did not reference messaging apps, we did not include this as part of our analysis. OAIC staff reviewed policies and procedures of the 7 remaining agencies to determine whether they:

- specifically addressed the use of messaging apps

- included a policy on whether the agency permitted the use of messaging apps for work purposes

- addressed security classification of information that could be communicated via messaging apps

- addressed whether work information could be communicated via a personal account or if a stand-alone work account was required (and if a work account was required how that would be created)

- referenced archival requirements (such as recordkeeping obligations or disposal authority)

- referenced the specific functionality and formats of a particular app

- described processes for information capture and storage

- addressed FOI requirements (such as ensuring they were searchable for FOI purposes).

Appendix B: Transmittal letter

Dear Attorney-General,

Consumer messaging apps – such as Signal, WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger and Telegram – are an established feature of personal and professional communication. In conducting Information Commissioner reviews of freedom of information (FOI) requests, my office has exercised statutory functions relevant to Australian Government officials’ use of messaging apps. These apps present novel considerations for key pillars of our democratic system of government including transparency and accountability.

Recognising the use of messaging apps by government and the application of statutory obligations under the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (FOI Act); the Privacy Act 1988 (Privacy Act) and the Archives Act 1983 (Archives Act) and, in consultation with the Director General of National Archives, I have prepared a report for you under section 7(a) of the Australian Information Commissioner Act 2010 (AIC Act). A primary objective of this report is to provide information, advice and assistance to agencies relevant to the use of messaging apps.[38]

In order to prepare this report, I reviewed the practices of 22 Australian government agencies, finding:

- messaging apps are an established feature of digital communications in the Australian public service:

- 16 (73%) of the 22 respondent agencies expressly permitted the use of messaging apps for work purposes. 3 (14%) agencies expressly prohibited their use and 3 agencies did not have a position about their use

- agency staff are using messaging apps for work purposes:

- 16 (84%) of the 19 agencies that do not prohibit the use of messaging apps for work purposes confirmed that it is likely that messaging apps are in use by staff

- agencies have developed a preference for a particular messaging app:

- 12 (75%) of the 16 agencies expressly permitting the use of messaging apps endorsed encouraged or communicated a preference for the use of Signal (one of these also endorsed, encouraged or preferred WhatsApp)

- despite being an established feature of government agency communication, the use of messaging apps is not well supported with policies and procedures that reflect statutory obligations[39]:

- 8 (50%) of the 16 of agencies that expressly permitted the use of messaging apps had policies/procedures to support the use of messaging apps.

In reviewing the policies and procedures of the 7 agencies that provided their policies, I found:

- the majority (5 out of 7) of agency policies address essential security classification requirements

- the majority (6 out of 7) of agency policies do not address essential archive requirements

- the majority (5 out of 7) of agency policies do not adequately address FOI search requirements

- the majority (5 out of 7) of agency policies do not require the use of official accounts or devices when using messaging apps for work purposes.

Informed by these findings I made recommendations for Australian Government agencies to strengthen their compliance with their recordkeeping, FOI and privacy obligations when using messaging apps. I recommend:

- Agencies should review existing policies or develop a policy to clearly set out whether or not they permit the use of messaging apps for work purposes.

- Agencies that permit the use of messaging apps for work purposes should have policies and/or procedures about the use of those apps that address information management, FOI, privacy and security considerations that:

- adequately address FOI requirements, including those relevant to accessing records under the FOI Act, and recordkeeping obligations under the Archives Act

- explain how to extract information from messaging apps, either in response to an FOI request or to store on recordkeeping systems

- address whether accounts created for official purposes, using phone numbers linked to agency-issued phones, are required to communicate official information

- adequately address privacy requirements including those relevant to accessing and amending records under the Privacy Act

- address the security classification of information that messaging apps can handle

- explains when the disappearing message functionality must be turned off, and how to do so

- confirm whether staff are permitted to use messaging apps to communicate the personal information of members of the public.

- Agencies should examine the features of messaging apps necessary to support official work. They should conduct appropriate due diligence on apps, consider the implications for communications with other agencies, and develop policies and procedures specific to individual apps.

- Agencies that permit the use of messaging apps should conduct due diligence to ensure any preferred messaging app collects and handles personal information appropriately, this may be achieved through a privacy threshold assessment.

In addition to the expertise offered by National Archives this report would not have been possible without the engagement and support of Australian Government agency heads.

My office will work with National Archives of Australia to support agencies to understand their recordkeeping, FOI and privacy obligations. In addition, my office will revisit this issue in 2 years (2027) to understand how use of messaging apps in the Australian Public Service has evolved.

Yours sincerely,

Elizabeth Tydd

Australian Information Commissioner

27 February 2025

[1] FOI Act s 4

[2] ibid

[3] FOI Act s 3(3)

[4] FOI Act s 6C

[5] Essential statutory requirements under the FOI Act, Privacy Act and Archives Act

[6] Archives Act s 24 and s 31

[7] APS Values and Code of Conduct in practice, Section 4.7 and National Archives’ Information Management Standard for Australian Government, Principle 2

[8] PS Act s 3

[10] The Archives Act stipulates that the lawful disposal or destruction of information received or created by Australian Government agencies will (in most circumstances) require the permission of National Archives.

[11] FOI Act s11

[12] With some exceptions, such as intelligence agencies

[13] FOI Act s3

[14] Privacy Act Schedule 1, Australian Privacy Principle s 12.1, subject to exceptions set out in s 12.2

[15] While archiving had been common practice in the Commonwealth since federation, and the first steps to create a consolidated national archives began in 1942, there was no legislated mandate until 1983. See Our history | naa.gov.au

[16] Taken from 40 years on, mobile phones still pushing consumers' buttons (accessed 3 February 2025)

[17] When we refer to officials, we include Australian Government Ministers, Commonwealth public servants and ministerial staffers, who (with limited exceptions) are bound by both the FOI Act and the Archives Act

[18] For example, Signal, WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger and Telegram can send messages that disappear

[19] Archives Act s 3(1)

[21] Privacy Act Schedule 1 Australian Privacy Principle (APP) 12

[22] FOI Act s6C

[24] Archives Act s 24

[25] Under s 4 of the FOI Act, the definition of document includes ‘any article on which information has been stored or recorded, either mechanically or electronically’

[26] We did not ask this of agencies where their use was prohibited and note this was a subjective question based on what the officer responding to the questionnaire had been exposed to.

[27] See National Archives’ Information Management Standard for Australian Government and Getting started with information management | naa.gov.au

[28] See Chapter 9 of PSPF Release 2024 - Guidelines

[31] See Managing social media and instant messaging (IM) | naa.gov.au and Appraisal and sentencing | naa.gov.au

[32] A records authority is a legal instrument that allows agencies to make decisions about keeping, destroying or transferring Australian Government records. Records authorities are used to determine how long to keep records and provide permission for the destruction of records once this time has passed.

[33] Any destruction should be in line with each agency’s records management policies and National Archives-issued records authorities

[34] See Part V of the FOI Act

[35] See APPs 12 and 13 in Schedule 1 of the Privacy Act

[36] A significant sample size based upon approximately 200 Australian government agencies

[37] Two agencies did not provide responses (the Department of Social Services and the Australian Human Rights Commission) and one agency provided a nil response (the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care)

[38] s8(d) and 9(2) AIC Act

[39] FOI Act, Privacy Act, Archives Act