-

On this page

Report to the Attorney-General

February 2012

Prof. John McMillan, Australian Information Commissioner

Introductory pages

The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) was established on 1 November 2010 by the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner Act 2010.

All OAIC publications can be made available in a range of accessible formats for people with disabilities. If you require assistance, please contact the OAIC.

ISBN 978-1-877079-95-5

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, this report is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en).

This publication should be attributed as: Office of the Australian Information Commissioner, Review of charges under the Freedom of Information Act 1982 – Report to the Attorney-General – February 2012.

Enquiries regarding the licence and any use of this report are welcome.

Office of the Australian Information Commissioner

GPO Box 2999

CANBERRA ACT 2601

Tel: 02 9284 9800

TTY: 1800 620 241 (no voice calls)

Foreword

The capacity of an agency or minister to impose an access charge under the Freedom of Information Act 1982 is always at the centre of debate about the operation of the Act.

FOI requests can impose a substantial administrative burden on agencies and divert resources from other functions. Access charges are a way of controlling and managing demand for documents and defraying some of the cost of FOI to government.

On the other hand, FOI charges can discourage or inhibit the public from exercising the legally enforceable right of access to government information granted by the FOI Act. The objective of the Act to make government open and engaged with the public will be hampered if it is too expensive or cumbersome for people to make FOI requests.

Balancing those competing interests has always been important, yet difficult. Major reforms to the FOI charges framework were introduced in 2010 to strike a new balance between public access and the administrative demands on government. The Australian Government, recognising the evolving significance of this issue, foreshadowed at the time that I would be asked to commence a review of the FOI charges framework within a year of the reforms commencing on 1 November 2010.

This report concludes that further change to FOI legislation is needed. A new charges framework could enable the FOI Act to work better in providing public access to government information without impairing the other responsibilities of agencies and ministers.

The reform proposals in this report arose from a valuable consultation exercise conducted by the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner with Australian Government agencies, advisory committees, members of the public and community organisations. I thank them for their valuable assistance to my office in this review.

The prevailing theme in all consultation for this report was that the FOI Act is a vital statute that must be supported by government and made to work in an optimal manner. My recommendations for reform are framed in that spirit. I commend them to the Australian Government for close consideration.

Prof. John McMillan

Australian Information Commissioner

10 February 2012

About this review

The terms of reference for this review were issued by the Minister for Privacy and Freedom of Information, the Hon Brendan O'Connor MP, on 7 October 2011. At the time the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) was in the portfolio of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. The OAIC was transferred to the portfolio of the Attorney-General's Department in late October 2011.

Terms of reference for review of charges under the Freedom of Information Act 1982

Review by the Australian Information Commissioner

I, Brendan O'Connor, Minister for Privacy and Freedom of Information, request the Australian Information Commissioner to review the charges regime under the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (FOI Act), including considering the following matters:

- the role of fees and charges in FOI

- the impact on applicants and agencies of the current charging regime

- options for change to the fees and charges regime;

- whether the decision to impose charges, or the nature or level of charges imposed, should vary according to the nature of the request or the applicant; and

- any other related matter.

The review should be undertaken in consultation with users of FOI and other stakeholders, Australian Government agencies and the Information Advisory Committee (when appointed). The review should have regard to

- the objects of the FOI Act

- the costs to agencies in processing FOI request

- practices in other Australian and international jurisdictions.

The report should be provided by 31 January 2012.

[Authority: section 8(f) of the Australian Information Commissioner Act 2010]

Discussion paper

I commenced this review by releasing a discussion paper on 31 October 2011 on the OAIC website at www.oaic.gov.au.[1] The discussion paper outlined the scope of the review, the background and elements of the charging framework, the estimated costs incurred by agencies in processing FOI requests contrasted with fees and charges collected, and provided an overview of charging practices in other Australian and international jurisdictions.[2] The discussion paper included a list of questions concerning the role of charges under the FOI Act (see Appendix A of this report). Submissions on the discussion paper were requested by 21 November 2011. The discussion paper was widely advertised, including through the use of the OAIC's Twitter account,[3] govdex community[4] and OAICnet mailing list. [5]

The OAIC received a total of 23 submissions from agencies and applicants. Submissions as published are listed in Appendix B. Late submissions were accepted until the end of December 2011.

Consultation

I conducted consultation sessions during November and December 2011 with the public, Australian Government agencies, the Information Advisory[6]and the Administrative Review Council (ARC).[7] Details of the consultation sessions are listed at Appendix C.

Executive summary and recommendations

Background to this inquiry

The Freedom of Information Act 1982 (FOI Act), upon commencement in 1982, authorised agencies and ministers[8] to impose charges for providing access to documents. The type and scale of charges were set out in the Freedom of Information (Charges) Regulations 1982 (Charges Regulations). In deciding on a charge an agency is to observe the stated objective of the FOI Act to facilitate public access to government information promptly and at the lowest reasonable cost (s 3(4)).

Changes have been made only four times to the charges provisions. The first change occurred in 1985 when an FOI application fee was introduced. Next, in 1986 a charge for decision making was introduced, and the current scale of charges was set. The third change was in 1991, when a cap was imposed on the charge that could be levied for a request for personal information. The most recent changes in 2010 were part of an extensive reform of the FOI Act, and were of two kinds:

- application fees were removed from FOI access requests, applications for internal review, and requests to amend or annotate personal records

- FOI charges were removed from access requests for personal information, for the first five hours of decision making time for other requests, and where an agency fails to notify a decision on a request within the prescribed processing period.

At the time of introducing these recent substantial reforms into the Parliament, the Government foreshadowed that it would ask the Australian Information Commissioner to review the charges regime within a year of the 2010 reforms commencing. This review commenced in October 2011, and involved publication of a discussion paper, consultation with the public and Australian Government agencies and advisory committees, and consideration of written submissions.

Main issues raised in inquiry

Issues that were highlighted by agencies in submissions and during consultations included:

- the suitability of the charges scale, which has not altered since 1986

- the need to simplify the charges framework

- the useful role that charges play in initiating a discussion with applicants about narrowing and refining the scope of broad requests, and the difficulties agencies face in using s 24AB of the FOI Act (the 'practical refusal' mechanism) to achieve the same effect

- the problem of large and complex applications from specific categories of applicants who use the FOI Act rather than rely upon other means to obtain information (such as law firms that use the FOI Act as a form of discovery, and members of parliament, journalists, researchers and the media)

- the need for further guidance from the OAIC regarding the application of the FOI Act provisions for waiving and reducing charges, particularly in assessing an applicant's claim of financial hardship or that disclosure would be in the public interest.

Applicants and members of the public, by contrast, emphasised the importance of:

- minimising cost barriers to the exercise of the democratic right of access conferred by the FOI Act

- ensuring that charges do not discriminate against economically disadvantaged applicants

- preventing the introduction of a full cost-recovery principle for FOI charging.

Various proposals for reform were made, including:

- simplifying the charges scale by combining some existing charges into a single hourly processing charge

- introducing a graduated charging scale under which the charge increases based on the time an agency spends in processing a request

- prescribing a ceiling on the amount of time an agency is required to spend on processing a request

- charging according to the amount of information released

- charging according to the category of applicant

- imposing an FOI application fee and abolishing all other processing charges.

Guiding principles to underpin a new charges framework

Fees and charges play an important role in the FOI scheme. It is appropriate that applicants can be required in some instances to contribute to the substantial cost to government of meeting individual document requests. Charges also play a role in balancing demand, by focusing attention on the scope of requests and regulating those that are complex or voluminous and burdensome to process.

On the other hand, full cost-recovery would be incompatible with the objects of the FOI Act and would strike unfairly against large sections of the community. This has been accepted during 30 years of the FOI Act, as the reported fees and charges collected by agencies represent only 2.08% of the estimated total cost of administering the FOI Act (1.68% in 2010–11). The FOI reform objective in 2010 was to further reduce the cost to the community of obtaining government information and to promote greater transparency in government.

A balance must be struck, but the current method in the FOI Act and Charges Regulations of striking that balance is inadequate. The charging framework is not easy to administer; charges decisions cause more disagreement between agencies and applicants than seems warranted; in some cases the cost of assessing or collecting a charge is higher than the charge itself; and the scale of charges is outdated and unrealistic.

This report proposes four principles to underpin a new charges framework:

- Support of a democratic right: Freedom of information supports transparent, accountable and responsive government. A substantial part of the cost should be borne by government.

- Lowest reasonable cost: No one should be deterred from requesting government information because of costs, particularly personal information that should be provided free of charge. The scale of charges should be directed more at moderating unmanageable requests.

- Uncomplicated administration: The charges framework should be clear and easy for agencies to administer and applicants to understand. The options open to an applicant to reduce the charges payable should be readily apparent.

- Free informal access as a primary avenue: The legal right of access to documents is important, but should supplement other measures adopted by agencies to publish information and make it available upon request.

Recommendations for a new charges framework

Recommendations are made in Part 5 of this report to replace the current charges framework in the FOI Act and Charges Regulations with a new framework that can be summarised as follows:

- Administrative access: Agencies are encouraged to establish administrative access schemes that enable people to request access to information or documents that are open to release under the FOI Act. A scheme should be set out on an agency's website and explain that information will be provided free of charge (except for reasonable reproduction and postage costs).

- FOI application fees: To encourage people to use an administrative access scheme prior to using the FOI Act, an agency may in its discretion impose a $50 application fee if a person makes an FOI request without first applying under an administrative access scheme that has been notified on an agency's website. A person who applies under an administrative access scheme and is not satisfied with the outcome or who is not notified of the outcome within 30 days may make an FOI request without paying an application fee. The agency's exercise of the discretion to impose a $50 application fee would not be externally reviewable by the Information Commissioner (IC reviewable), nor subject to waiver on financial hardship or public benefit grounds.

- FOI processing charges: No FOI processing charge should be payable for the first five hours of processing time (which includes search, retrieval, decision making, redaction and electronic processing). The charge for processing time that exceeds five hours but is less than 10 hours should be a flat rate of $50. The charge for each hour of processing after the first 10 hours should be $30 per hour.

- Ceiling on processing time: An agency should not be required to process a request that is estimated to take more than 40 hours. The agency must consult with the applicant before making that decision. This ceiling will replace the practical refusal mechanism in ss 24, 24AA and 24AB. An agency decision to impose a 40 hour ceiling would not be IC reviewable, though the agency's 40 hour estimate would be reviewable.

- FOI access charges: Specific access charges should apply for other activities, such as supervising document inspection ($30 per hour), providing information on electronic storage media (actual cost), postage (actual cost), printing ($0.20 per page) and transcription (actual cost).

- Personal information: There should be no processing charge for providing access to documents that contain an applicant's personal information, but personal information requests should be subject to the 40 hour ceiling applying to other requests.

- Waiver: The specified grounds on which an applicant can apply for reduction or waiver of an FOI processing or access charge should be financial hardship to the applicant, or that release of the documents would be of special benefit to the public. An agency may waive a charge in full or by 50% or decide not to waive. An agency would also have a discretion not to impose or collect an FOI application fee or processing or access charge; the exercise of that general discretion would not be an IC reviewable decision.

- Reduction for delayed processing: Where an agency fails to notify a decision on a request within the prescribed statutory period, the FOI charge that is otherwise payable should be reduced by 25% if the delay is seven days or less, 50% if more than seven but up to and including 30 days, or 100% for a delay of more than 30 days.

- Review application fees: There should be no application fee for internal review. Nor should there be an application fee for IC review, if an applicant first applies for internal review and is not satisfied with the decision or is not notified of a decision within 30 days. If an applicant applies directly for IC review when internal review was available, a fee of $100 should be payable. The fee should not be subject to waiver.

- Indexation: All FOI fees and charges should be adjusted every two years to match any Consumer Price Index change over that period, by rounding the fee or charge to the nearest multiple of $5.

Explanation of the proposed changes

The proposed changes are explained fully in this report. The theme throughout is that applicants and agencies can equally benefit from a new charges framework that is clear, easy to administer and understand, encourages agencies to build an open and responsive culture, and provides a pathway for applicants to frame requests that can be administered promptly and attract little or no processing charge. There are three primary ways for bringing this change about.

The first is by encouraging agencies to develop, and applicants to use, administrative access schemes before resorting to the formal legal processes of the FOI Act. Administrative schemes can play a key role in meeting the objectives of the FOI Act. They can provide quick and informal information release in a way that can reduce the cost both to applicants and agencies. Importantly, they complement and do not detract from the legally enforceable right of access under the FOI Act. In fact, the discussion that occurs between applicants and agencies at the administrative access stage can assist the smooth operation of the FOI Act and bring about targeted and quicker document release if FOI processes are later used.

The second is by introducing a new scale of FOI charges that is clear and straightforward to administer. The new scale will markedly benefit applicants whose requests can be processed in less than 10 hours. Personal information requests will remain free of processing charges. A new ceiling of 40 hours on processing time would replace the 'practical refusal' mechanism in the FOI Act that makes it difficult to decide when a complex or voluminous request imposes an unreasonable administrative burden upon an agency. This will also provide a clear standard for deciding when consultation should occur between an agency and an applicant about revising and narrowing the scope of a request that appears unmanageably large.

The third is by reinforcing the important role that internal review can play in quickly and effectively resolving a disagreement between an applicant and an agency about a document request. Internal review is generally quicker than IC review and enables an agency to take a fresh look at its original decision. An applicant could still apply directly for IC review but would be required to pay an application fee of $100 (subject to some exceptions). This proposal builds on a changing mood within government since the 2010 reforms to attribute greater importance to internal review and to treat it as a valuable step in resolving access requests.

Part 1: The Freedom of Information Act 1982 and the existing charges regime

Overview of the FOI Act

The declared objects of the FOI Act are:

- to give the Australian community access to information held by government, by requiring agencies to publish that information and by providing for a right of access to documents

- to promote Australia's representative democracy by increasing public participation in government processes, with a view to promoting better-informed decision making and increasing scrutiny, discussion, comment and review of government activities

- to increase recognition that information held by government is to be managed for public purposes and is a national resource

- to ensure that powers and functions in the FOI Act are performed and exercised, as far as possible, so as to facilitate and promote public access to information, promptly and at the lowest reasonable cost.[9]

The FOI Act promotes government accountability and transparency by providing a legal framework for people to request access to government information. This right of access extends to government information about policy making, administrative decision making and government service delivery. The Act also gives people the right to access information that government holds about them, and to request corrections to that information if they consider it to be incorrect, incomplete, misleading or out of date.

The FOI Act commenced operation on 1 December 1982. It applies to all Australian Government agencies, with certain exemptions as set out in s 7. Ministers (including parliamentary secretaries) and their offices are also covered by the FOI Act, although the Act applies only to the 'official documents' of a minister and not those of a personal nature or relating to the minister's activities as a member of a political party or a member of Parliament. Section 3A of the FOI Act states that the Act does not prevent or discourage an agency or minister from releasing documents, including documents that are exempt under the FOI Act, as long as there is no legal restriction on disclosure.

Reform of the FOI Act occurred in 2010 following a 2007 election commitment by the Australian Labor Party. The Freedom of Information (Reform) Act 2010 and the Australian Information Commissioner Act 2010 (AIC Act) commenced on 1 November 2010. These Acts introduced major changes to the FOI landscape, including:

- introducing a presumption of openness and maximum disclosure, based on publication of information and the release of information upon request unless there is an overriding reason not to do so

- requiring the proactive release of an increased range of information through a new Information Publication Scheme (IPS) for Australian Government agencies from 1 May 2011

- establishing the independent statutory positions of the Australian Information Commissioner and Freedom of Information Commissioner (FOI Commissioner)

- removing application fees for FOI requests, internal review of FOI decisions, and requests to amend or annotate personal records

- removing charges for FOI requests for personal information and making the first five hours of decision making time free for all other requests.

These Acts also established the OAIC, an independent statutory agency headed by the Information Commissioner with the support of the FOI Commissioner and the Privacy Commissioner. The former Office of the Privacy Commissioner was integrated into the OAIC. The OAIC combines the functions of information policy and independent oversight of FOI and privacy protection in a single agency to promote open government and advance the development of consistent, workable information policy across Australian Government agencies.

Within the OAIC, the FOI Commissioner is primarily responsible for FOI functions such as day-to-day administration of FOI enquiries and complaints, undertaking merit review of FOI decisions, investigating complaints about FOI administration and monitoring agency compliance with the FOI Act. Agencies must have regard to guidelines issued by the Information Commissioner under s 93A of the FOI Act (FOI Guidelines).[10]

Avenues for accessing information within the FOI framework

Formal requests under the FOI Act

Section 11 of the FOI Act declares that every person has a legal right to obtain access to documents of an agency and official documents of a minister, other than exempt documents. Section 15 sets out the requirements for making an FOI access request, including that the request must be in writing, state that the request is an application for the purposes of the FOI Act, provide adequate information to allow the agency or minister to identify the document, and give details of how notices should be sent to the applicant (s 15(2)). The request can be delivered to an agency or minister in person, by post or electronically (s 15(2A)).

Section 15 also obliges agencies and ministers to assist any person who wishes to make a request or whose request does not meet the above requirements (s 15(3)). Where a person has made a request that should have been directed to another agency or minister, there is an obligation to help the person direct the request to the appropriate agency (s 15(4)).

Agencies and ministers have 14 days after receiving a request to notify the applicant that it has been received (s 15(5)(a)) and 30 days to notify the applicant of a decision on the request (s 15(5)(b)). The 30 day processing period can be extended where consultation with other entities is needed before making a decision on the request (s 15(6), (7)), the applicant agrees to an extension (s 15AA), the request is complex or voluminous and the Information Commissioner approves an extension (s 15AB), or where the time for making a decision has expired without the applicant receiving notice of the decision (s 15AC).

The FOI Act also recognises that access to government information can occur through means other than a formal request for documents:

- an agency can establish procedures for current or former staff to obtain access to personnel records (s 15A)

- information can be published by an agency under the IPS

- agencies and ministers can provide access to information outside the formal FOI Act process (s 3A).

Those avenues are discussed further below.

Agency employee access to personnel records (s 15A)

Section 15A of the FOI Act provides that a current or former employee of an agency must use a procedure established by the agency for providing access to personnel records before using the formal FOI request process. A person who is not satisfied with the outcome or who is not notified of the outcome within 30 days may then make an FOI access request (s 15A(2)).

Section 15A was enacted in 1991,[11] following recommendations made in 1986 by an interdepartmental committee (IDC) review of the costs and workload associated with FOI, and in 1987 by the Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs review of the FOI Act.[12] The IDC review examined the costs of FOI and calculated that in 1984–85, about 15% of FOI access requests were for access to personnel records of current or former Commonwealth employees seeking information relating to their employment.[13] The proposed new procedure would bring an estimated saving of $850,000 per year.[14] The Senate Committee review accepted that savings could be made but considered it important to retain the legally enforceable right of access.[15]

Some agency websites highlight the existence of administrative access schemes for staff wishing to access their personnel records. [16] The Department of Defence (DoD), for example, has established a scheme that applies to current and former members of the Australian Defence Force and current and former employees of the Department. Staff can request their service and medical records, discharge certificates, recruitment file, psychology records and other kinds of documents. If a request falls outside the scope of the administrative access scheme, staff are advised to make an FOI access request and are provided with links to FOI request forms and general information about FOI.[17]

The Information Publication Scheme

The 2010 FOI reforms established the IPS for Australian Government agencies, commencing on 1 May 2011.[18] The IPS is intended to increase public access to government information and promote a pro-disclosure culture within government by requiring the publication of some categories of government information and encouraging the proactive publication of other information. The IPS requires agencies to publish accurate, up to date and complete information about their:

- structure

- functions

- statutory appointments

- annual reports

- consultation arrangements

- documents to which access is routinely given under the FOI Act

- information routinely provided to Parliament

- operational information, meaning information that assists the agency to exercise its functions or powers in making decisions or recommendations that affect members of the public, including agency rules, guidelines, practices and precedents relating to those decisions and recommendations

- details of the agency's contact officer.[19]

Agencies can also choose to publish other information through their IPS.[20] This includes information that may be of interest or benefit to the public, for example, information that increases public understanding of an agency's decisions, policies or programs.[21]

Agencies are not required to publish in their IPS entry information that would be exempt under the FOI Act.[22] However, agencies retain a discretion to release information, including information exempt under the Act, so long as this is not restricted by other legal obligations. Agencies are to be guided by the principle that government held information is declared by the Act to be a national resource, to be made available wherever possible in an accessible and usable fashion.[23]

Agencies can charge for access to information or documents released under the IPS only if the data cannot be made available to download from a website and the agency has incurred specific reproduction or incidental costs in making the data available under the IPS.[24] However, apart from the IPS, it is still open to agencies to make publications and information available for purchase by the public (s 12(1)(c)).

The IPS is complemented by a requirement on agencies and ministers to publish on their websites information that has been released in response to each FOI access request (subject to certain exceptions), known as a 'disclosure log'.[25] Inherent in both the IPS and disclosure log requirements is the principle of facilitating equal public access rather than exclusive individual access to government information.

The IPS and disclosure log requirements may, in time, reduce the number of individual document requests to agencies. More fundamentally, they will increase public availability of government information in line with the objects of the FOI Act.

Access to government information apart from the FOI Act

Section 3A of the Act provides that it does not limit access to or the publication of government information outside the processes set down in the Act.

A common approach by agencies to releasing information outside the FOI access request process is via agency online service portals. The portals facilitate both client access to personal information and agency–client transactions. They allow clients to access and update their personal information without charge and also provide agencies with a low-cost alternative to providing access to personal information via the FOI Act.

The Australian Government is seeking to strengthen its online service delivery capabilities through the Australian Government Online Service Point (AGOSP) Program. AGOSP is a $42.4 million Budget initiative that will enhance the australia.gov.au website to provide people with simple, convenient access to government information, messages and services. The enhancements to australia.gov.au will include a single sign-on service, allowing people to access online services from multiple government agencies through one account, an advanced online forms capability, and a National Government Services Directory, providing a comprehensive list of government services.

The Department of Human Services (DHS) provides channels for individuals to access personal information held by DHS agencies outside the FOI Act. The website directs individuals wishing to access their personal information to Centrelink's Online Services, Child Support Agency (CSA) Online, and Medicare Services Online. These portals allow individuals to login and access their information, and in some cases to amend information that is incorrect. For example, the CSA Online portal allows users to view and update their personal CSA details, view and print most CSA letters, and access account details, including a history of payments made and received. Medicare's online services portal allows users to lodge a Medicare claim, update bank account details, update personal details (email, phone, address and more), and view both Medicare claims history and 'Care Plan' access history.

The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) also provides access to information via online service portals. The ATO's three portals are the Business Portal, the Tax Agent Portal, and the BAS Agent Portal. These portals enable secure access to and correction of certain information held by the ATO. The ATO's FOI web page also explains when a person may not need to make an FOI request to access information, for example how people can access recent notices of assessment or recent tax returns, as well as taxation rulings, determinations, decision impact statements, and law administration practice statements.

Current FOI landscape

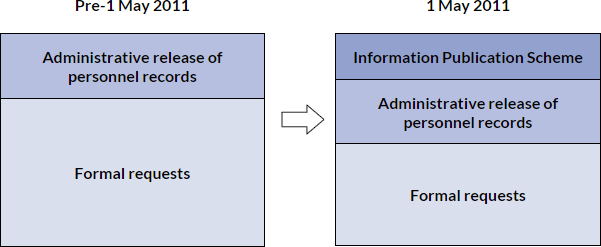

Prior to the 2010 reforms, many documents were released only after an FOI access request or a request for personnel records under s 15A. The IPS provides a third mechanism. This is represented in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: The impact of the IPS on the FOI landscape

Pre-1 May 2011

- Administrative release of personnel records

- Formal requests

1 May 2011

- Information Publication Scheme

- Administrative release of personnel records

- Formal requests

Current charging framework applicable to FOI access requests

An agency or minister has a discretion to impose or not impose a charge for access to a document requested under s 15 of the FOI Act. Any charge imposed must not exceed the charges set out in the Charges Regulations. When determining the appropriate charge, the agency or minister must take account of the 'lowest reasonable cost' objective as set out in the objects clause of the FOI Act (s 3(4)).

The FOI Guidelines state that a charge must not be used to discourage an applicant from exercising the right of access conferred by the FOI Act.[26] Charges should fairly reflect the work involved in providing access to documents. Agencies should have sound record keeping practices so that an agency's documents can be readily located and retrieved when an FOI request is received.[27] Applicants are not to be disadvantaged by poor or inefficient record keeping.[28]

The following is an outline of the key features of the current charges regime. A summary of the main legislative provisions is set out at Appendix D. For the purpose of this report, an 'application fee' refers to a fee that accompanies an FOI access request or request for review. A 'charge' refers to an amount imposed and collected for processing an FOI access request or providing access in a particular form.

Application fee for FOI access requests

There is no application fee for making an FOI request. In particular, agencies and ministers cannot impose a fee for an application to access a document or amend or annotate personal information.

Scale of charges

The FOI charges that an agency or minister may impose for an initial access decision cover activities such as search and retrieval time, decision making time, retrieval and collation of electronic information, transcription, photocopying, replay, inspection and delivery of documents.

In 1982, the original charges regime incorporated an hourly charge for search and retrieval but no charge for decision making. In part, it was reasoned that as time went by, agencies would need less time for decision making due to increasing familiarity with the legislation and adoption of different attitudes and practices at the time that documents were created.[29] The Senate Committee's 1979 report on the FOI Bill also expressed concern that charges for decision making time would be applied inconsistently and that those agencies that were less disposed to openness would likely spend more time on decision making. [30] In the Committee's view:

It hardly seems fair or just, in a Bill designed to confer rights of access, that an agency's charges are inversely related to its commitment to the philosophy underlying the Bill.[31]

In 1986, an hourly charge was introduced for agency decision making. The IDC review of the costs and workload associated with FOI in 1986 and the Senate Committee's review of FOI in 1987 were in favour of an hourly decision making charge. The Senate Committee noted that there was little data available on the amount of time that agencies spent on decision making but that it was appropriate that some degree of cost recovery was attempted. [32] However, the Committee recommended a cap on the number of hours that could be charged for decision making time as a means of addressing the risk that applicants end up paying for 'agency inefficiency, obstructionism [and] unjustified caution'.[33] While the hourly charge for decision making time was kept, no upper limit was introduced for requests involving non-personal information.

Figure 2 sets out the current charges. They are not subject to regular indexation and have not increased since November 1986.

Activity item | Charge | Schedule |

|---|---|---|

Search and retrieval: time spent searching for or retrieving a document | $15.00 per hour | Part I, Item 1 |

Decision making: time spent in deciding to grant or refuse a request, including examining documents, consulting with other parties, and making deletions | First five hours: Nil Subsequent hours: $20 per hour | Part I, Item 5 |

Electronic production: retrieving and collating information stored on a computer or on like equipment | Actual cost incurred by the agency or minister in producing the copy | Part I, Item 3 |

Transcript: preparing a transcript from a sound recording, shorthand or similar medium | $4.40 per page of transcript | Part I, Item 4 |

Photocopy: a photocopy of a written document | $0.10 per page | Part II, Item 2 |

Other copies: a copy of a written document other than a photocopy | $4.40 per page | Part II, Item 3 |

Replay: replaying a sound or film tape | Actual cost incurred in replaying | Part II, Item 5 |

Inspection: supervision by an agency officer of an applicant's inspection of documents or hearing or viewing an audio or visual recording | $6.25 per half hour (or part thereof) | Part II, Item 1 |

Delivery: posting or delivering a copy of a document at the applicant's request | Actual cost | Part II, Item 8 |

Notification and collection of charges

Section 29(1) of the FOI Act provides that an applicant must be given notice in writing when an agency or minister decides that the applicant is liable to pay a charge. The notice must contain certain information, including the applicant's right to contend that the charge is wrongly assessed or should be reduced or waived.

When notifying an applicant of a charge, an agency or minister may require the applicant to pay a deposit (ss 29(1), 29(3), reg 13). The deposit cannot be higher than $20 if the notified charge is between $25 and $100, or 25% of a notified charge that exceeds $100 (reg 12). The agency or minister can defer work on the applicant's request until the deposit is paid or a decision is made to waive the charge following a request from the applicant.[34]

If an applicant is liable to pay a charge, the charge should be paid before the applicant is given access to documents (s 11A(1)(b), reg 11(1)). An exception applies if the charge is for supervising an applicant's personal inspection of documents or hearing or viewing an audio or visual recording (reg 11(2)). Payment of the charge cannot be required in advance of the inspection or viewing, unless the agency or minister has made a decision under reg 9(3) estimating the probable length of the period of inspection or viewing.[35]

Exceptions

There is no charge for an individual seeking access to their personal information. Personal information is defined in s 4(1) of the FOI Act as 'information or an opinion (including information forming part of a database), whether true or not, and whether recorded in a material form or not, about an individual whose identity is apparent, or can reasonably be ascertained, from the information or opinion'. The information may be private in nature or publicly known. It may be factual, descriptive or an opinion about that individual. The decisive quality is the connection between the information and an individual.[36]

A document that contains an applicant's personal information can fall within this exemption even if the document contains non-personal information. If the personal information forms a small part of a document and an agency or minister can reasonably be expected to expend extra time or resources in providing access to the entire document, it may be appropriate to impose a charge for providing access to the part that does not contain personal information. Before doing so, the agency or minister should consult the applicant about narrowing the scope of the request to that part of the document that contains the applicant's personal information.[37]

There is no charge where a minister or agency fails to meet the prescribed statutory processing period for making an FOI decision. The statutory processing period (30 calendar days) may be extended where a minister or agency needs to consult with an affected third party, by agreement with the applicant or where the Information Commissioner grants an extension.

As noted in Figure 2, there is no charge for the first five hours of the time spent in making an access decision (Schedule, Part I, Item 5). There is no equivalent free time for the search and retrieval of documents.

Correction, reduction or waiver of charges

An applicant who receives a notice advising that a charge is payable may apply in writing to the agency or minister for the charge to be corrected, reduced or waived (s 29(4)). If an applicant contends that a charge has been wrongly assessed, the central issue to be considered is whether relevant provisions of the FOI Act and the Charges Regulations have been correctly understood and applied.[38] If, on the other hand, an applicant contends that a charge should be reduced or waived, the agency or minister has a general discretion to consider, among other matters:

- whether payment of the charge, or part of it, would cause financial hardship to the applicant or a person on whose behalf the application was made

- whether giving access to the document in question is in the general public interest or in the interest of a substantial section of the public (s 29(5)).[39]

The application should set out the applicant's reasons for contending that the charge has been wrongly assessed or should otherwise be reduced or waived (s 29(1)(f)(ii)).[40]

The agency or minister must provide a written notice of a decision regarding a review of a charge to the applicant within 30 days. If the decision is to deny the applicant's request in whole or in part, the notice of decision must set out the reasons for the decision and the applicant's right to seek internal or Information Commissioner review (IC review) of that decision or to make a complaint to the Information Commissioner and the procedure for doing so (s 29(8)–(10)).[41]

Internal and external review

There is no fee for applying for internal review, review by the Information Commissioner or for making a complaint to the Information Commissioner.

By contrast, a fee is payable under reg 19 of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Regulations 1976 (AAT Regulations) for an application to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) for review of a decision of the Information Commissioner. The fee, which is increased every two years in line with the Consumer Price Index (CPI), was $777 as at 31 January 2012. The fee can be reduced to $100 in certain circumstances that include an application by a person receiving legal aid or holding a Commonwealth health care or pensioner concession card (reg 19(6)), or payment of the fee being waived by a Registrar, District Registrar or Deputy District Registrar of the AAT on financial hardship grounds (reg 19(6A)).[42]

No fee is payable if the decision was made under the FOI Act in relation to a document which relates to a decision under Schedule 3 to the AAT Regulations. Decisions listed under Schedule 3 includes decisions about Commonwealth workers' compensation, family assistance and social security payments and veterans' entitlements.

Fees and charges collected under the FOI Act

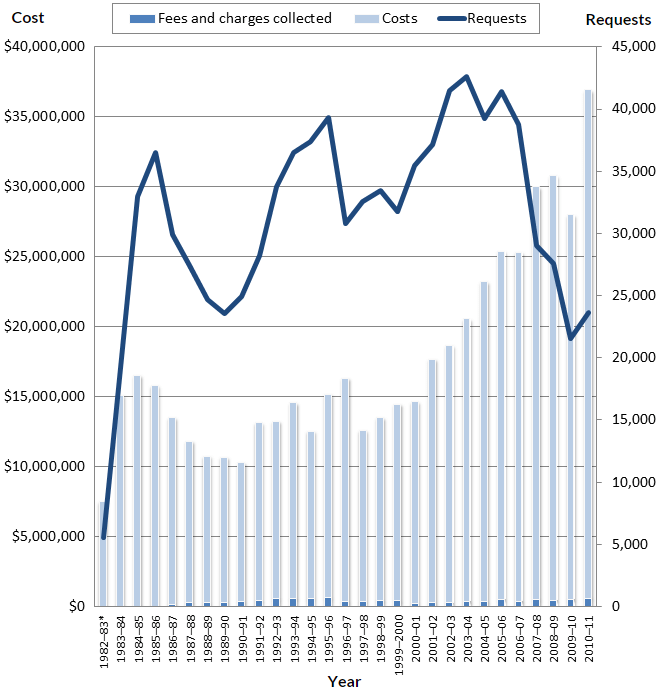

Between the commencement of the FOI Act in 1982 and 30 June 2011, agencies reported a total cost of $498,364,739 to process the 906,639 FOI requests received during this period. The total cost includes staff hours spent on FOI matters and estimates of non-labour costs directly attributable to FOI, such as training and legal costs. However, these figures are an estimate and it is generally understood that agencies rarely keep exact records of hours spent by officers on FOI matters and other non-labour costs incurred.

The total amount of fees and charges collected since the commencement of the FOI Act represent 2.08% of the estimated total cost of administering the FOI Act during the same period. Fees and charges collected in any year have consistently been less than 5% of the total cost of administering the FOI Act, ranging from 0.33% (1982–83) to 4.91% (1994–95), with the yearly average at 2%. Figure 3 sets out the total costs, requests and fees and charges collected since 1982–83.[43]

Figure 3: Total costs, requests and fees and charges collected since 1982–83

* Seven months of 1982–83 only.

Part 2: The role of fees and charges under the FOI Act

Background

Fees and charges have been a part of FOI in Australia since 1982. During the life of the Act, there have been efforts to find the right balance between principles of cost recovery, 'user-pays', accessibility, citizen rights and government accountability.

Early on, before the full impact of the legislation was known, charges were viewed as a way of managing demand for government documents. In 1979, the Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs stated:

There are practical reasons also why a power to levy charges must exist. If documents could be obtained free of charge, there is a distinct danger that agencies could be beleaguered with requests for most documents that are brought into existence.[44]

Charges provided a means of deterring frivolous and excessively broad FOI requests. The original FOI charges regime established an hourly charge for search and retrieval, along with charges for document inspection and copying. In 1985 and 1986, FOI charges were amended to incorporate, first, an application fee and then an hourly charge for decision making on FOI requests.

On the subject of FOI charges, the second Committee report in 1987 expressed concern that:

… too much emphasis has been placed upon economic factors (such as cost recovery) at the expense of the admittedly unquantifiable social (and political) benefits derived from the right of access under the Act.[45]

Further, the Committee agreed with the view it expressed in its 1979 report, that charges needed to strike a balance between the 'user-pays' principle (as a deterrent to trivial, overly-broad or poorly framed requests) and ensuring that charges did not limit the range of people able to use the legislation.[46]

The 1987 Senate Committee report recommended capping the number of hours an agency could charge for search and retrieval and decision making time, even though the agency may spend further time processing a request. Placing a cap on chargeable hours would mean that applicants would be less likely to be penalised for an agency's inefficiency or poor record keeping. In addition, applicants would know in advance the maximum possible charge that might be imposed.

Amendments to the Charges Regulations in 1991 partially implemented this recommendation by capping the charge for requests for personal information of the applicant, while leaving the charges for all other requests uncapped.[47]

In 1994, the Attorney-General commissioned the Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) in partnership with the ARC to review FOI legislation. The ALRC-ARC report stated that charges should be balanced with democratic accountability. The ALRC-ARC noted:

A strict application of the user-pays principle would almost certainly guarantee that the Act would fail in its objectives. Yet it can be argued that totally free access may place an unreasonable financial and administrative burden on agencies. In the Review's view, applicants should make some contribution to the cost of providing government-held information but that contribution should not be so high that it deters people from seeking information. The fees and charges regime should reflect the fact that the FOI Act is primarily about improving government accountability and the public's participation in decision making processes, not about generating revenue or ensuring cost recovery.[48]

The ALRC-ARC report recommended abolishing charges for processing requests for personal information. Charges (including the application fee) should be retained for other requests, with the application fee being used as credit towards any charges imposed. It also recommended that the application fee for internal review be abolished and that the scale of charges be set by an FOI Commissioner.[49]

Changes in 2010

The 2010 reforms to the FOI Act made significant amendments to the charges regime, some of which implemented recommendations made by the ALRC-ARC. The amendments aimed to reduce the cost of making a request for access under the Act.[50] These included:

- abolishing application fees for requests and internal review

- abolishing charges for requests involving an applicant's own information

- providing the first five hours of decision making time free of charge for requests involving non-personal information

- providing that no charge is required to be paid where an agency or minister fails to notify a decision within a period prescribed in the Act (including a permitted extension period).[51]

Views on the role of fees and charges

As part of this review, the discussion paper invited comments on the role of fees and charges under the FOI Act. Many agencies emphasised the need for a balance between meeting the 'lowest reasonable cost' object of the Act and having applicants contribute to the sometimes significant cost of processing FOI requests.[52] For example, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) noted:

The lowest reasonable cost objective implies that applicants should bear some of the costs associated with making a request. In our view, this approach strikes an appropriate balance between the rights of applicants against the significant costs borne by agencies in processing requests that is ultimately subsidised by the Government.[53]

In a similar vein, the Treasury submitted:

While it is not reasonable to expect a[n] FOI applicant to bear the full cost of processing a request, we note that the Government is currently facing considerable fiscal constraints. This makes it particularly important that the benefits to the public of disclosure of information are balanced against the costs of providing that information.[54]

Most of the agencies that made submissions accepted that the charges regime should not, and was never intended to, operate as a full cost recovery arrangement, although some suggested that charges needed to be increased to better reflect the actual cost to the agency of providing access. NBN Co pointed out that '[w]hile FOI charges were never meant to be full cost recovery, it is clear that there is a significant imbalance between current charges and costs to agencies'. Other agencies noted that charges had not been updated in line with CPI.[55]

In contrast, both Greenpeace Australia Pacific (Greenpeace) and the Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) pointed out that charges played only a minor role in recouping agency costs. Greenpeace submitted that:

Such a recovery rate is so nominal that one must ask whether the benefits of recouping costs through charges and fees is disproportionate to the negative impact they have on access to information that concerns the public.[56]

In addition, PIAC submitted: 'The idea of recovering costs from FOI users is at odds with the idea that FOI legislation is about the fundamental right of individuals to access information'.[57]

PIAC quoted a Queensland Electoral and Administrative Review Commission report, which stated that access to information was a fundamental democratic right:

FOI is not a utility, such as electricity or water, which can be charged according to the amount used by individual citizens. All individuals should be equally entitled to access government-held information and the price of FOI legislation should be borne equally.[58]

Almost all agencies noted the practical benefit of imposing charges and the way that they encouraged applicants to focus the terms of their requests.[59] As the CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation) pointed out:

[T]he imposition of charges plays an important practical role in facilitating discussions with the applicant to revise the scope of FOI requests ensuring that the resource burden on agencies is manageable, without issuing a s 24AB(2) notice.[60]

A notice under s 24AB(2) is a notice sent by an agency or minister to notify the applicant of their intention to refuse to process a request on the basis that the work would substantially and unreasonably divert the agency's resources from its other operations or substantially and unreasonably interfere with the performance of the minister's functions.[61] This mechanism was also referred to by Greenpeace:

Targeted and effective legal frameworks already exist for dealing with the problem of excessively broad requests (see, eg s 24 of the FOI Act). Already departments use s 24 as a mechanism to initiate discussions that attempt to satisfy the information needs of the applicant and reduce the burden on the department through negotiating a more focused FOI request. This is a more precise, democratic and inclusive tool.[62]

Greenpeace further submitted that financial disincentives not only discriminate against economically disadvantaged applicants, but are a very blunt instrument with which to focus FOI applications. PIAC agreed and expressed concern that 'the existing costs in some cases may deter reasonable requests, and not just potentially vexatious requests'.[63]

The Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) and the Federal Court of Australia (FCA) also emphasised the importance of simplicity in any charges framework, with the FCA submitting:

Adding complexity increases the administrative costs with no return to agencies for actual processing time, is an unnecessary disincentive to potential applicants and increases the risk of dispute.[64]

The role of fees and charges: Guiding principles

Fees and charges play an important role in the FOI scheme. However, the current charging framework does not strike an appropriate balance for agencies and applicants. The framework is not easy to administer; charges decisions cause more disagreement between agencies and applicants than seems warranted; in some cases the cost of assessing or collecting a charge is higher than the charge itself; and the scale of charges is out-dated and no longer realistic.

This report proposes four principles to underpin a new charges framework.

Support of a democratic right

Freedom of information is an essential part of democratic government in Australia. A substantial part of the cost should be borne by government. Providing information to the public upon request supports transparent, accountable and responsive government, and should be treated as a core business function of each government agency. Document requests must nevertheless be regulated by FOI charges, to prevent an unreasonable administrative burden that could detract from other agency responsibilities. The FOI charging framework must strike a balance between providing ready public access to government information and the cost and resource implications of doing so.

Lowest reasonable cost

Public access to government documents should be provided at the lowest reasonable cost to applicants. Every person should have the opportunity to request government information, particularly personal information that should be provided free of charge (subject to limited restrictions). The scale of charges for other requests should not discourage applicants from exercising their legal right to obtain access to government documents. A key purpose of charges should be to moderate unmanageable requests.

Uncomplicated administration

The charges framework should be clear and easy for agencies to administer and for applicants to understand. There should be as few charging categories as practicable. The cost to an agency of assessing a charge should not exceed the amount of the charge imposed. It should also be clear to applicants when a charge can be imposed and the steps available to the applicant to reduce a possible charge. The charging framework should minimise disagreement between applicants and agencies.

Free informal access as a primary avenue

Government agencies should be committed to making information readily available to the public, both generally and upon request. The legal right of access to documents created by the FOI Act is an important democratic right, but the public should not be required to always access that right in order to obtain government information. Agencies should be equipped to deal with requests for information outside the formal FOI request process, and support applicants in obtaining information both through FOI and by other means.

Administrative access schemes provide an appropriate avenue for free and fast information release. Information technology has changed the way government information is created and published, by the introduction of new tools to search, retrieve and collate information, and use of the internet to distribute that information at relatively low cost through government online service portals and the publication of data on websites. These technologies have fundamentally changed the context in which FOI operates in Australia. The 2010 reforms to the FOI Act, including the introduction of the IPS, have further moved FOI towards emphasising the proactive release of government information.

The FOI access request process must remain a vital part of the legal framework for facilitating public access to government information. However, encouraging alternative channels for information access that are, for the most part, free of charge can reduce reliance on formal FOI processes and place greater emphasis on informal information exchange between agencies and the public.

Part 3: Summary of issues and proposals considered

Overview

This Part is divided into the following sections which follow the framework set out in the discussion paper:

- general concerns with the current charges framework

- application fees

- scale of charges

- imposition of charges

- exceptions

- collection of charges

- correction, reduction and waiver

- other issues.

This Part summarises the issues and proposals for reforms of the charges regime as submitted to the OAIC in response to the consultation questions in the discussion paper. The consultation questions are listed at Appendix A. Those that made submissions are listed at Appendix B. Charging practices of other Australian and international jurisdictions are summarised at Appendix E. The views expressed in submissions about the role of fees and charges are discussed in Part 2.

General concerns with the current charges framework

In submissions and during consultation sessions, agencies identified various issues which impacted on their workload. These issues included:

- the need to simplify the charging framework

- the useful role that charges play in initiating a discussion with applicants about narrowing and refining the scope of broad requests, the difficulties agencies face using s 24AB of the FOI Act (the 'practical refusal' mechanism) and in treating multiple requests as a single request under s 24(2)

- the problem of large and complex applications from specific categories of applicants who use the FOI Act rather than relying upon other means to obtain information (such as law firms that use the FOI Act as a form of discovery, and members of parliament, journalists, researchers and the media)

- the need for further guidance from the OAIC regarding the application of the FOI Act provisions for waiving and reducing charges, particularly in assessing an applicant's claim of financial hardship or that disclosure would be in the public interest.

Applicants and members of the public, by contrast, emphasised the importance of:

- minimising cost barriers to the exercise of the democratic right of access conferred by the FOI Act

- ensuring that charges do not discriminate against economically disadvantaged applicants

- preventing the introduction of a full cost recovery principle for FOI charging.

Application fees

Application fees for FOI requests and requests for internal review were abolished in 2010. In this review, agencies were asked whether the abolition of fees had any effect on FOI requests and requests for internal review. Agencies were also asked whether it was appropriate to reimpose application fees for FOI access requests and reviews, and if so, the appropriate level of fee that should be imposed. Applicants, on the other hand, were invited to comment on whether an application fee would deter them from making an FOI access request or from seeking review of an adverse FOI decision.

The discussion on application fees is grouped under the following categories:

- application fees for FOI access requests

- application fees for FOI access requests involving personal information

- application fees for internal review

- application fees for IC review

- application fees for AAT review.

Application fees for FOI access requests

Ten agencies noted an overall increase in FOI requests following the 2010 reforms.[65] Many agencies, including the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (DAFF), DEEWR, DoD, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), DHS and the Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism (DRET), noted that it was difficult to determine if the removal of application fees alone had contributed to the higher volume of requests.[66]

The Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency (DCCEE), the Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA) and DFAT linked the abolition of application fees to a rise in request splitting, where applicants deliberately lodge multiple FOI requests to capitalise on free decision making time.[67] This was also mentioned in other agency submissions.[68] One agency at a consultation session described a case where an applicant lodged 440 requests about 10 different subject matters in a single email, along with the instruction that they be considered separately so as to receive the free decision making time for each request.[69] DCCEE also described an applicant who submitted 700 FOI requests in five months.[70]

The Department of Finance and Deregulation (DoFD), DFAT and IP Australia suggested that, since application fees had been abolished, applicants seemed more likely to make a request and then withdraw it after receiving an estimate of applicable charges.[71] Other agencies said that they had not noticed a correlation. For instance, DEEWR suggested that applicants were more likely to enter into negotiations to reduce the scope of a request rather than withdraw it altogether.[72]

Some agencies expressed support for the reinstatement of an application fee. IP Australia submitted that a nominal application fee, reviewed on an annual basis and keeping pace with inflation, would help reduce the number of speculative and unreasonable requests.[73] DoFD noted that without an application fee, applicants are more likely to lodge requests without full consideration of the actual documents being sought or whether the documents are available through other means. It proposed a fee of $30–$40 that should remain stable for a specified period (for example, three to five years) and could be offset against the first hour of charges payable as per the New South Wales (NSW) model.[74]

DoHA proposed that any fee or charge should be significantly higher than the previous $30 fee in order to discourage frivolous applications, offset against the total processing costs.[75] DFAT suggested that a fee of $20–30, indexed to CPI, would be appropriate,[76] while DRET suggested a $50 fee.[77] Ms Megan Carter noted that if application fees were to be imposed, a range of $15–30 would be a reasonable level, and would not deter her from making an application.[78] DFAT also proposed that consideration be given to whether applicants who are not Australian citizens or residents should pay an application fee.[79]

Some agencies were opposed to the reintroduction of application fees. CSIRO, DEEWR and DHS submitted that application fees are contrary to the objects of the FOI Act.[80] DoD was of the view that the administrative burden of collecting a fee, including collection, acknowledgement, reporting and addressing requests for remission of the fee, would far exceed the fee itself.[81] NBN Co expressed similar concerns about the administrative cost of collecting application fees, while DRET noted that the abolition of application fees has made the administration of FOI requests more efficient, as it removed the administrative processes that were previously required to process relatively small amounts of money.[82]

PIAC suggested that application fees sit uncomfortably with the public right to access government information, and that government should meet this cost in the interests of transparency.[83] Greenpeace, while advocating the elimination of all fees and charges, submitted that it would not oppose the introduction of a flat fee of $35 with no additional charges, as per the Tasmanian model.[84] DEEWR opposed a flat application fee, labelling it as 'inequitable' because it does not consider the varying costs required to process different FOI requests.[85]

The Global Mail described application fees as an 'inherent barrier' to making FOI requests.[86] Greenpeace suggested that fees and charges have a 'clear chilling effect' on FOI applications from not-for-profit organisations.[87] The National Welfare Rights Network (NWRN), which provides information, advice and casework assistance to their clients in the area of social security law, expressed concern that application fees would serve as a deterrent to FOI requests. They also made a similar point to other agencies noted above about the costs involved in administering an application fee compared to the actual fee imposed.[88]

Application fees for FOI access requests involving personal information

Agencies at the consultation sessions agreed that personal information applications should be exempt from FOI charges. One agency suggested that access to personal information should be free as it is entwined with the right under the FOI Act to request access to and amendment and annotation of personal information. Some agencies expressed concern about instances where an applicant, who had obtained all their personal information documents, kept lodging new FOI requests for the same documents.

Most submissions proposed that there should be no application fee for personal information requests. Ms Carter noted that while it is not appropriate to have an application fee for such requests, a number of areas associated with access to personal information need to be addressed, including the disproportionate use of the right to access personal information by current and former public servants often engaged in protracted disputes with their agencies.[89]

Application fees for internal review

Most agencies suggested that there should not be an application fee for internal review. DEEWR, DoD, DHS and DRET submitted that an applicant should have the opportunity to seek an internal review of an access refusal or access grant decision free of an application fee.[90] DHS argued that the same policy basis in the objects of the FOI Act for not imposing an FOI application fee (that information held by the Government is a national resource) also applied to internal review application fees.[91] DoD described internal review as 'a means of enhancing accountability within an agency' and suggested that reintroducing application fees could discourage applicants from seeking internal review.[92] PIAC noted that fees for internal review are not applied in other jurisdictions, such as the United Kingdom (UK), Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT).[93]

One agency at a consultation session suggested that internal review should be encouraged over IC review as applicants are 'more engaged' at internal review. Other comments from agencies about the value of internal review referred to the relationship between internal and IC review (discussed in the next section).

In contrast, some agencies' submissions supported the reintroduction of application fees for internal review. DFAT supported its reintroduction in recognition of the time and resources required for such a review.[94] IP Australia considered that a fee for internal review helps to ensure that the party seeking the review is focused on what they seek to achieve.[95] DoFD noted concerns that the lack of internal review application fees encourages applicants to lodge applications regardless of the soundness of the original decision.[96] Similarly, CSIRO, citing an example where an applicant requesting internal review responded via email within two minutes of receiving a complex access decision, suggested that a nominal fee ($50 subject to biennial increase) should be charged for internal review, except where the internal review relates to a decision regarding the applicant's personal information.[97] Ms Carter noted that if internal review fees were imposed, a reasonable fee of $20 would not deter her from making an application for internal review but a fee of more than $50 probably would.[98]

NBN Co suggested that, instead of an application fee, agencies could be allowed to charge for time required to undertake an internal review, with the first five hours of time provided free.[99]

Application fees for IC review

Agencies generally supported the introduction of an application fee for IC review, with some agencies emphasising the significant costs to agencies in preparing for an IC review. DoD argued that there is currently a discrepancy in the administrative process where there are no application fees for making an application for external review by the Information Commissioner, yet applications for review by the AAT require a $777 application fee.[100]

CSIRO emphasised the resources and timeframes involved in responding to an IC review, and suggested that a nominal fee for IC review would encourage applicants to consider the agency's decision and whether IC review would provide a substantially different outcome.[101] DCCEE submitted that an application fee for IC review would encourage applicants to seek internal review with the agency that made the original decision,[102] while DRET suggested that a nominal fee for an IC review application may have the effect of reducing the backlog of matters currently being handled by the OAIC.[103] The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (DPMC) also discussed the potential correlation between the lack of an application fee for IC review and the number of IC review applications received since the 2010 reforms.[104] Ms Megan Carter submitted that if IC review fees were imposed, they should be set low, for example at $20.[105]

Several agencies raised the possibility of imposing an application fee for IC review where internal review is not sought first. DoD and DRET mentioned this model,[106] with DRET specifically noting that internal review 'is less burdensome on all involved and can produce a quicker outcome for the applicant'.[107] Without making specific reference to application fees for internal and IC review, ACCC suggested that IC review should only be available if an applicant has previously sought internal review, unless an applicant has not received a response to a request for internal review within 30 days. [108]

Some agencies noted that if application fees were imposed for IC reviews, internal reviews should also carry an application fee. DoFD suggested that introducing a fee for IC review alone 'would likely only transfer the burden from one review mechanism to another without regard to the soundness and merits of the decision'.[109] Similarly, IP Australia suggested that all application fees should be treated in the same manner (that is, there should be an application fee at every level of the request and review process).[110]

Application fees for AAT review

This review did not consider the application fees set by the AAT. No submissions were made regarding the appropriateness of an AAT application fee or the appropriate level of fees.

Scale of charges

The consultation questions specifically asked:

- whether the scale of charges was appropriate, and if not, what level of charges should be imposed

- whether the scale of charges should be subject to increase or be capped

- whether a different approach to charges should be adopted, including whether the charge should vary according to the nature of the applicant or the time taken to process a request, or whether a cap or 'ceiling' should apply to the number of hours taken to process FOI access requests.

General concerns about the current scale

There was general consensus among agencies that the existing scale of charges should be simplified. Submissions suggested that a simplified charging model would be easier for agencies to administer and result in more uniform charging outcomes for applicants. As noted in Part 2, FCA submitted that any changes which increase the complexity of the current scale will increase administrative costs for agencies, discourage potential applicants and increase the risk of disputes between applicants and agencies.[111]

As outlined below, a number of agencies viewed a standard hourly processing charge as a means of simplifying the existing charges regime.

Most agency submissions also expressed concern that the scale of charges was not commensurate with the costs incurred by agencies in processing requests.[112] Treasury suggested that 'the most important principle is that the applicant should make a non-negligible contribution' to the cost of processing an FOI request.[113]

Submissions from community groups, including Greenpeace and PIAC, noted by contrast that charges were such a small return on agency costs that they should not be levied at all.[114] Both recommended that all fees and charges for FOI requests be abolished. Greenpeace submitted that 'financial disincentives discriminate against economically disadvantaged applicants'.[115]

Charges other than decision making and search and retrieval

Only six submissions referred to the charges for electronic production, transcripts, photocopies and other copies, replay, inspection and delivery. These are summarised below.

Electronic production

No submissions raised concerns with charging electronic production at actual cost.

Transcription

Ms Megan Carter and DoD both recommended that transcription be charged at actual cost.[116] NBN Co suggested that charges for transcription should not be levied per page but according to the time spent transcribing.[117] DHS submitted that: 'The cost of producing a transcript should reflect the commercial cost of having a transcript prepared,' and noted that the current figure did not reflect this.[118]

Photocopies

Ms Megan Carter and DoD recommended that photocopying be increased from the current charge of $0.10 per page to $0.20 per page.[119] DHS also suggested that the $0.10 charge for photocopying may not be high enough and noted that the Federal Magistrates Court charges $0.67 per photocopied page for comparable functions.[120]

Other copies

NBN Co recommended that agencies be able to charge the market rate to produce non-standard copies while DoD suggested other copies be charged at actual cost.[121] No other submissions raised concerns about the current approach to charging for a copy of a written document other than a photocopy.

Replay

No submissions raised concerns about the current approach to charging for replay of sound and film recordings.

Inspection

NBN Co and DHS both submitted that the current charge of $6.25 per half hour for inspection of documents was not an appropriate rate and that the charge needed to reflect the cost of having an officer present to supervise inspection.[122] DoD suggested that inspection of documents be charged at $30 per hour.[123]

Delivery

No submissions raised concerns about the current approach to charges for posting or delivering a document to an applicant.

Indexation

Most agency submissions proposed that the scale of charges be increased appropriately and kept up to date.[124] Some submissions suggested that indexing charges to CPI or inflation would be appropriate,[125] while others suggested conducting annual or biennial increases or reviews of charges. [126] Greenpeace submitted that:

… unless charges and fees are to be increased to the point at which they substantially recoup the administrative costs of the FOI Act – which would effectively destroy access to information for not-for-profit organisations – [indexation] seems to make little sense. [127]